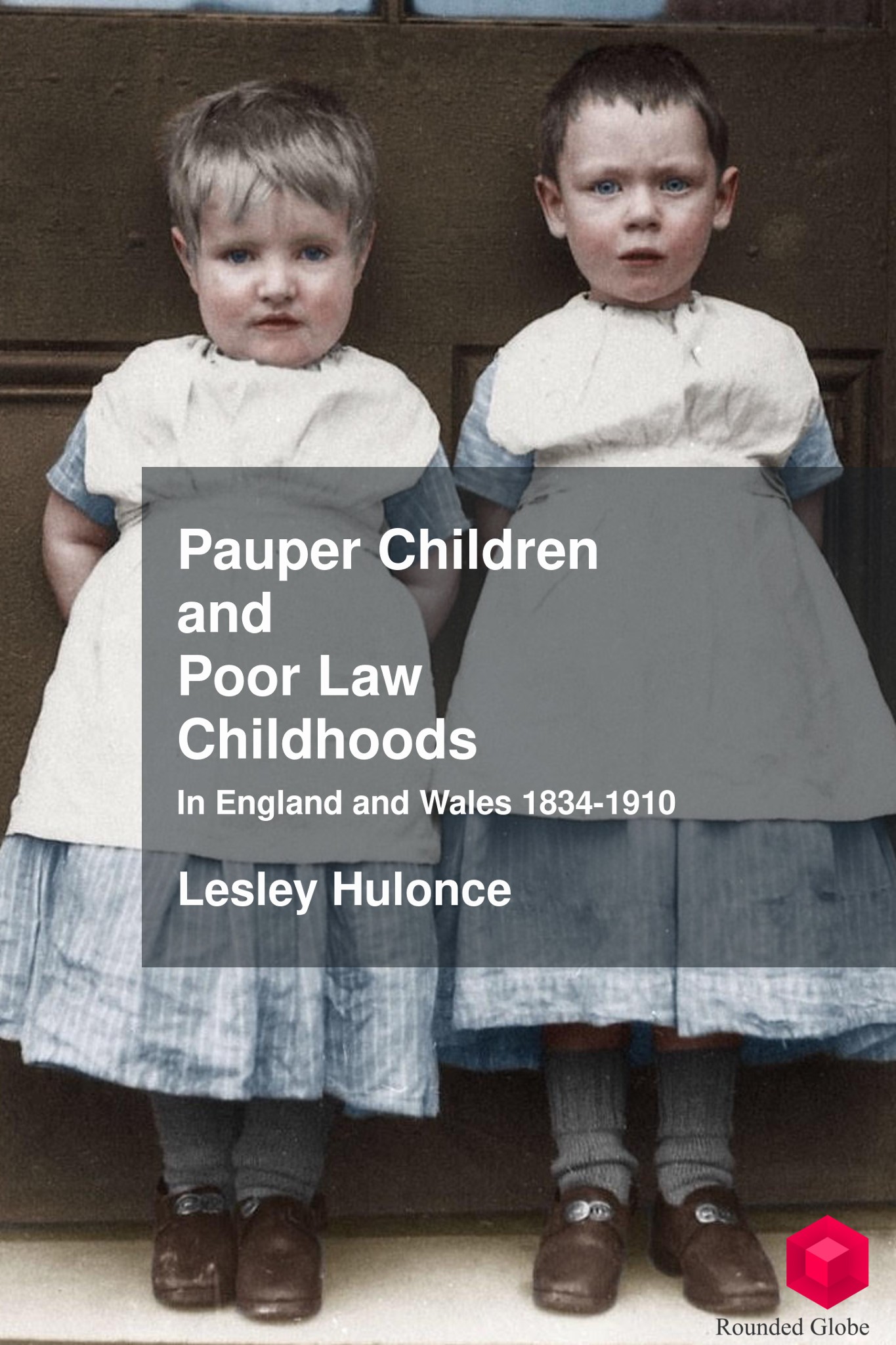

Pauper Children and Poor Law Childhoods in England and Wales 1834-1910

Lesley Hulonce

Rounded Globe

Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Children who belong to the state

- Part One: Pauper children and poor law institutions

- Part two: Pauper children in the Community

- Part three: Pauper children and philanthropic institutions

- Timeline

- Bibliography

- About the Author

A brief note about traditional academic publishing

A few months ago I gave a talk about Victorian prostitution to a local history group. I had a terrible cold but I talked to an audience of around 200 for an hour. It was well received with so many questions and comments that we were booted out by the next group. I had agreed a nominal fee of £35 but I was informed that as it was ‘part of my working day’, I should waive it. Yes, really, I think I’ll pass a hat around next time…

This won’t be news to many academics, particularly those in the early years of their career. However, it was a liberty too many taken with my time and labours. Since I finished my PhD in 2013 I’ve told my daughter excitedly that I’d been asked to write this and that, and her reaction is invariably ‘how much are they paying you?’ The answer is nearly always ‘nothing’.

I submitted a book proposal to a major international publisher and was waiting for their comments and hopefully a contract. The publishers commissioned reviews from historians and they were very encouraging; Reviewer 1 said they had read my two sample chapters in one sitting, and even the rather picky Reviewer 2 recommended publication.

When the publisher offered me a contract I was excited and delighted, especially as it had taken me two years to finally submit the proposal. Then I asked how much the book would be, and I was told £65. If I wanted a particular cover image I would be expected to pay for the permissions myself. As it is the first book looking at all the diverse strategies of care for pauper children it was expected to sell well, so I decided to look around for other publishing options.

I hope many historians will also be encouraged to take different routes when publishing their research, and maybe then the traditional academic publishing industry will begin to change.

For readers who are unfamiliar with the poor laws please see the timeline and key dates at the back of the book.

Acknowledgements

This is a very long list, especially because of the sheer length of time I have taken to revise my PhD thesis into Pauper Children. It actually started as my MA thesis, ‘Children who belong to the state’ in 2008, where I began my fascinating journey into the history of children, and in particular the residents of Cockett Cottage Homes in Swansea.

I must first thank my children Joshua and Emma who have grown up alongside my academic adventure. They were just 13 and 12 respectively when I was studying for my MA and are now 21 and 19. They attended lectures with me when child care failed or when they were unable to go to school, and without their patience, support and love I could not have completed any of my degrees. Thank you, Pauper Children is for you.

When I first began my undergraduate degree in 2003, the eminent historian Professor David Howell encouraged me greatly; he was the first person to call me a ‘historian’ and I thank him for all his help over the years and hope I have done him proud.

Professor Chris Williams has been a source of inspiration, enablement and humour since I took his module ‘The South Wales Coalfield’ in 2007. As my PhD Supervisor he provided helpful (if a tad pedantic) feedback and taught me to never say ‘due to’, and always to insert a full stop at the end of footnotes. My students all know my horror when they refrain from doing this. Chris is a world renowned scholar and I thank him for everything he has done for me over the years.

I have been fortunate to know Professor David Turner since my undergraduate years, and remember especially our larks in his MA module ‘the making of modern sexualities’. Five women and David attempted to navigate the complexities of sexual behaviour in the early modern period by competing to find the rudest primary sources to bring to class for discussion. David’s examination of my PhD thesis was kind, insightful and helpful. Thank you David, your writing is always exquisite and you use beautiful words, I can only hope some of it has rubbed off on me.

I left the History Department after 10 years as a student and later as a lecturer. My colleagues there are some of the best teachers and researchers in the country. In particular I want to thank Huw Bowen, Martin Johnes, Evelien Bracke, Louise Miskell, Richard Hall, Mike Mantin, John Spurr, Deborah Youngs, Lucie Matthews Jones, and Stuart Clark.

Since August 2015 I have been lecturer in the history of medicine in the College of Human and Health Sciences at Swansea University. My new colleagues are supportive and generous and I want to thank particularly Chantal Patel (the most enabling boss anyone could have), Ceri Phillips, Head of College, for his financial support of my Children’s Welfare History Workshop, Michelle Lee, a force of nature, and my departmental colleagues Alys Einion, Susanne Darra, Angela Smith, Julia Parkhouse, Andrew Bloodworth, and Mark Jones.

My adventures in Twitter have resulted in many generous new friends and I must thank Dr Helen Rogers especially. Helen is a first-class scholar and teacher, and she has inspired me to include dramatised accounts in my work and to emulate her wonderful teaching and blogging practices. Helen’s suggestion that I might use the Burnett collection of working-class autobiographies has transformed Pauper Children.

I have haunted many archives, libraries and museums over the past ten years. My thanks go to Marilyn Jones and Gwilym Games of Swansea Central Library. The staff of West Glamorgan Archives Service, especially Elizabeth Belcham and David Morris, put up with me in my year with the guardians minute books, and I was so often there that the café staff offered me discount as they thought I was a member of staff. Swansea Museum is a treasure trove of artifacts and primary sources, and thanks to the staff and Gerald Gabb for their help.

Thanks to readers:

What a lovely lot historians are, many kind people have read my book and made helpful suggestions.

Neil Evans

Mike Mantin

Lucie Matthews Jones

Helen Rogers

Helen Snaith

Steve Taylor

David Turner

Thanks to my ‘lay’ readers for their perception and questions which have made the book much more understandable

Jim and Ingrid Ransome

David Hulonce

Thanks to our cats Lola, Harry, Ziggy and The Kitten for cuddles and insightful commentary, and to the Wales football team for providing welcome distraction during the UEFA Cup 2016. Oggie, oggie, oggie.

Introduction: ‘Children who belong to the state’1

In 1838 the London and Westminster Review informed its readers that the New Poor Law had proved to be a very popular theme for ‘grievance’ songs. The lyrics to several broadside ballads were printed including The English Poor Law in Force, which railed against the refusal of relief to a destitute family, and the self-explanatory Just Starve Us. The Review thought the lyrics to A Workhouse Boy were too ‘horrible for citation’; it told the story of how a pauper boy was killed and his body added to the Christmas soup.2 The Review concluded that these songs contained the ‘fiercest exaggerations’ of the charges that were being laid against the new poor laws.3 Ballads such as these, together with reports about the neglect of paupers, shaped popular opinion of an iniquitous new law. The Age periodical claimed that if the measures proposed by the Poor Law Commission were enacted, their opinions about ‘the united wisdom of the country’ would turn into ‘sentiments of indignation and horror’, while John Bull declared that the Poor Law Commissioners had ‘begun their reign of terror’.4 Between 1837 and 1842, The Times published more than two million words on the ‘new’ poor law’s administration, and related nearly 300 alleged ‘horror’ stories.5 By far the most evocative and enduring representation of the alleged evils of the new poor was the character of Oliver Twist created by Charles Dickens.6 As the London and Westminster Review reported, most of the reports, songs and literary representations of this new law were exaggerated, but the cruel and harsh reputation of the poor laws have proved as long-lasting as Dickens’ boy who dared to ask for more.

David Englander calls the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act ‘the single most important piece of social legislation ever enacted’. Historians have engaged with its complexities since its inception and the resulting scholarship is diverse and substantial.7 While the legislation itself and the minutiae of its administration can encourage somewhat dry scholarship, Pauper Children is mindful to avoid ‘stripping’ people of ‘their humanity’, and focuses on the human drama of paupers’ experiences within this hugely important Victorian law.8 The ‘new’ poor law was designed to deter paupers from applying for relief by including a ‘workhouse test’ whereby only the most necessitous and ‘deserving’ would accept the offer of the ‘House’ as the only relief available. In reality, many directives and recommendations issued by the central authorities were not always used by individual poor law unions. This is illustrated most starkly by the two main principles of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act proving unworkable in reality. The doctrine that all relief to able-bodied paupers and their families should only be given in workhouses was infeasible unless hundreds of new workhouses were constructed, and became impossible in times of high unemployment. The deterrent principle of ‘less eligibility’ intended that the standard of living in the workhouse was lower than that of the poorest independent labourer. In practice, diet and conditions in workhouses often exceeded those found in the homes of many poor families,9 but nonetheless a deterrent remained owing to the widely held punitive and humiliating reputation of the workhouse.

Nineteenth-century Britain was home to ‘great floods of children’ who throughout the course of the century constituted up to 40 per cent of the population.10 As children also made up between 30 and 40 per cent of recipients of poor law relief in nineteenth-century Britain, their impact on poor law resources and doctrine was substantial.11 Charles Dickens’ compassion for pauper children and his input into the poor law system extended well beyond his novel Oliver Twist. On a visit to a poor law school in 1850 he described how the children were ‘with minds and bodies destitute of proper nutriment, they are caught, as it were, by the parish officers, like half wild creatures, roaming poverty-stricken amidst the wealth of our greatest city; and half-starved in a land where the law says no one shall be destitute of food and shelter’.12 Similarly, schools inspector Jelinger Symons claimed that children had a ‘pure claim on public aid’, but while pauper children generated widespread pity for their condition the solution for its amelioration was contested.13 The often publicised plight of pauper children also generated attention from philanthropists and child welfare campaigners.14 These intersections between state aid and private philanthropy revealed competing ideologies of care and cost, and fostered class and gender friction.

While few scholars of the poor laws have ignored pauper children, they have receiving only passing attention in many works on wider poor law themes. Despite the burgeoning of histories of children and childhood being a flourishing area of historical scholarship, Frank Crompton’s Workhouse Children is the only monograph concerning children and the poor laws, and is confined to exploring their treatment in workhouses.15 The poor law central authorities in London along with many provincial poor law guardians saw the workhouse as unfit for the appropriate rearing of pauper children. The assessment of workhouses as ‘promiscuous environments’ was widespread, and the premise was reiterated by social purity activist Ellice Hopkins, who claimed that girls in the workhouse faced the especial threat of ‘the deepest degradation of all’.16 Child welfare campaigner Florence Hill was convinced that the association between girls and mothers of illegitimate children in workhouses was ‘polluting’ and she cited the similar views of many other commentators, including Edward Tufnell, Edward Senior and Jelinger Symons, as corroboration.17 Because of their association with pauper adults, it was thought that children were not only being insufficiently trained, but were ‘actually nurtured in vice’. It was thought inevitable that many workhouse children would grow up to be ‘thieves, prostitutes or paupers’.18 Symons had claimed that even when the children were in separate rooms from the other workhouse inmates, they could hear continually the ‘obscene conversation of the depraved portion of the adults’.19 This expectation continued into the twentieth century, and although the 1905-9 Poor Laws Royal Commission found little evidence, it was still assumed that workhouses contained a large number of prostitutes.20

If children were not corrupted by the workhouse, they were thought to be in grave danger of being ground down by apathy and losing any work ethic. One Welsh guardian referred to his workhouse as ‘that miserable hole’,21 and Florence Hill lamented ‘the inevitable consequences of ordinary workhouse life’ which equated to a ‘dulness [sic] of apprehension, ill-temper, a want of self-respect, and negligence as regards the care of property’.22 Charles Dickens thought that the ‘monotonous semi-prison life’ of the workhouse must ‘degrade and depress’ the minds of pauper children.23 Consequently, strategies were devised to move children out of workhouses across England and Wales. The vast majority of children supported by the poor laws had never been inside a workhouse, and they remained with their parents despite alleged embargoes of outdoor relief, and the parents themselves were often active agents where the education and welfare of their children was concerned.24 Children were boarded out with foster parents, some of whom were members of their extended families; many were sent to separate district schools or ‘cottage’ homes, and others spent whole or part of their childhoods in philanthropic and religious orphanages. The more ‘refractory’ pauper boys were sent to training ships; disabled children were often educated in specialist establishments such as institutions for the blind or deaf, and some poor law unions emigrated their children to Britain’s colonies.25

In essence Pauper Children supports the notion that most pauper children were not abandoned to beg for more food in workhouses, but that their upbringing; their reformation was carefully planned, managed and debated. It questions to what extent these varied strategies were a result of anxiety for the future economy in the production of ‘able labourers’, or care for the children themselves, although strategies of control and policies of goodwill were often interrelated. Perceptions of pity were used to justify more rate-payers’ money being spent on pauper children, and also to counter criticism that pauper children received advantages that were unavailable to the children of the independent poor. Although many conflicts concerning the care and education of these children who ‘belonged to state’ were unresolved, their proposed childhood was imagined as being ‘normal’, and was subsequently imposed upon them. In common with many fragile kin structures of the nineteenth century, the family networks of paupers were complicated and volatile.26

Pauper Children covers a long period, and as Hopkins claims, poor children were generally better off in 1900 than in 1800, but this was by no means a smooth progression. Some historians of the 1960s and 1970s, in their confidence of an unshakeable welfare state, analysed poor law provision as a weak precursor to the ‘cradle to the grave’ policies of the post-war Attlee Government and many works about social welfare provision prior to the 1990s invariably linked the word ‘welfare’ to the word ‘state’.27 As Daunton argues, assumptions that welfare history was ‘marching to a preordained end’ are problematic given the challenges to welfare provision in the 1980s and 1990s.28 Similarly, paradigms of ‘modernization’ and ‘unilinear’ explorations collapse when variations between poor law unions and sites of conflict between national policy and regional reactions to the relief of poverty are questioned, as they are in Pauper Children.29 This was a paradoxical era which saw laissez-faire competing with markedly increased intervention by the state.30 Poor law services were diverse, ambiguous and frequently patchy, and King, with the bemused fondness only a poor law devotee could display, calls them ‘endearingly riven with intra- and inter-regional differences’.31 The sheer enormity of contradictory decision making and behaviour is perhaps the reason why some scholarship of the poor laws has been opaque and indecipherable; the scale of figures, correspondence and bureaucratic paraphernalia that is available for the historian to consult still offers incompleteness, but in volume amounts to much more than could be done one lifetime.

Pauper Children builds on Alysa Levene’s brilliant study of the childhoods of the poor in eighteenth-century London.32 Similarly, Jane Humphries’ insightful and moving glimpses into the lives of pauper children as part of her study on child labour is a reminder of the power of working-class writing as a valuable source for the histories of children, and similar sources have been used in this study as much as possible.33 However, Pauper Childhoods takes care to foreground the child, rather than policies for his or her care, housing and education. In doing so I ask and answer questions concerning the children’s lives and hopes for their future, and memories of their past. I am also indebted to Lydia Murdoch’s arguments in Imagined Orphans which offers valuable comparisons between Dr. Barnardo and poor law care. Murdoch’s analysis of the ‘organisation of space’ within institutions, and her arguments concerning doctrines of middle-class domesticity embraced by poor law establishments which was envisaged as the polar opposite to the alleged chaotic and undomesticated homes of the poor echo my findings, and offer a framework for analysis.34

Although the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 applied to both Wales and England, its implementation and impact in the Welsh context has not been studied as exhaustively.35 Pauper Children will begin to redress this situation as it will explore the experiences of pauper children in both Wales and England. There are many fine works about poverty and childhood in London, and this book neither ignores nor foregrounds the capital. Although London has been called ‘a nation in itself’ in relation to poverty and the poor laws and many strategies for the care of pauper children originated in, or were inspired by trends in London’s ‘hotbed of innovation’. Consequently, these are important strategic developments which often influenced policies in the rest of England and Wales, and are explored in Pauper Children.36

Opinion among historians concerning the treatment of ‘looked after’ children in this period can vary widely. Hendrick claims that the pervasiveness of ‘legal violence’ in children’s institutions ‘nearly always’ resulted in not only corporal punishment but also sexual abuse.37 At the opposing end of the spectrum, Marianne Moore contends that the debates concerning industrial school and cottage homes systems were motivated not by social control but by benevolence, and as such presaged modern child protection services.38 Whilst agreeing with many of Moore’s findings, it is disingenuous to dismiss the subtle forms of social control inherent in the care of pauper children and Pauper Children questions the stability of homogeneous readings of the competing ideologies at work in poor law and child care systems of the time. Similarly, although Hendrick provides little evidence for his confident assertion above, the prevalence of sexual abuse in children’s homes uncovered by historical abuse enquiries begun in the 1990s and continuing at the time of writing in 2016, suggests that sexual abuse in children’s homes during the twentieth century was ubiquitous.39 This may indeed be so but nonetheless research conducted for Pauper Children has not revealed any evidence of institutionalised sexual abuse in the establishments under review, whether this is because vulnerable children were better protected by the Victorian system, or the evidence is too well hidden is difficult to establish.40

Pauper Children demonstrates how poor law guardians and managers of philanthropic institutions garnered support and funds by utilising the general sympathy that poor, orphaned and disabled children generated within the majority of the population. As Levene claims, the study of poor children is an activity ‘freighted with emotional overtones’.41 I do not subscribe to the views of historians such as Aries, Shorter and Stone who claimed for a lack of affection towards children prior to the modern period, although by the period covered by Pauper Children they argue that parental affection was well established, at least within the middle-class family.42 As Fletcher and Hussey argue, these historians’ ‘itch’ to argue linear change, and ‘progression’ has been misplaced.43 During this time ‘sentimentality’ flourished, especially when directed at ‘pathetic’ children; guardians were acutely aware of its power, as were the fund-raisers of philanthropic causes. It is also difficult and probably futile for historians of children to distance themselves completely from emotion concerning the children we research. Although, as Bown says, it has ‘rarely been respectable to stand up for sentimentality’, as we can still ‘fall prey to its lures’.44 Pauper Children claims that emotional investment, albeit accompanied by scholarly rigour, is unavoidable in the researching and interpretation of children’s histories. A project of this kind cannot be undertaken successfully without empathetic engagement with the children whose lives we seek to illuminate.45 Roper has also criticised detachment within scholarship relating to the First World War, where he claims that ‘the intensity of emotional experience’ might tempt historians ‘beyond linguistic codes’. However, as Roper claims, ‘empathetic connections’ between historian and subjects are problematic and we must be wary of projecting ‘the historian’s own unexamined projections onto the past’.46

Consequently, emotional affect will not sidestepped as it is necessary to engage with the feelings of children. I am inspired by the words of Ellen Ross in Love and Toil, whose seven year old son Zachary Glendon-Ross died in 1989 while she was researching her book. Ross claims that a historian can retain scholarly convention while experiencing emotional involvement with her historical subjects.47 While I argue that emotional engagement enhances histories of children, I take care to channel this emotion with academic detachment and not heroicise them nor construct for them ‘a mythical past’.48 The children will also be memorialised by naming as many as possible. In this I am informed and influenced by Ian Grosvenor’s argument that by being able to name children ‘we reclaim them as individuals’ and allow a voice to those ‘who remain largely silent’.49 The naming of children in print also confirms their existence in the same way as Roland Barthes’ claims that images demonstrate that a person has ‘indeed been’.50

It is unlikely that any of the extensive source base consulted for Pauper Children has not been mediated by those in authority. Jordanova warns us how historians ‘persist in searching for the voice of children themselves, in their diaries and autobiographies’ when there can be ‘no authentic voice of childhood speaking to us from the past because the adult world dominates that of the child’.51 We can however attempt to unravel children’s own experiences from multiple clusters of sources, undeniably mediated by the ‘adult world’, and, as Davis claims, ‘step forward from the margins’ to attempt readings of what has been revealed.52

The book is organised into three sections. Part one explores the experiences of pauper children in poor law institutions such as workhouses, district schools and later, cottage homes. Part two looks at the most used strategies for the care of pauper children in local communities including outdoor relief and boarding-out. Part three analyses how pauper children fared when they were sent by the guardians to privately run charitable establishments, and also examines the lives and future prospects of disabled children.

The treatment of children in workhouses is explored in the first chapter. The family circumstances of the children are analysed and their education compared with children of independent labourers. The workhouse was perceived as a site of moral contagion from which many unions sought either to remove them or attempt to nullify its effects by education, segregation and monitoring, and arguments and debates concerning separate establishments for pauper children took place over many years. Chapter Two analyses these debates and the lives pauper children could expect in these seemingly more child-friendly homes. This chapter claims that although family type institutions were perceived as leading the way in child welfare, by the early twentieth century these homes had equally fallen out of favour.

Chapter Three explores the much discussed and prevalent strategy of boarding-out pauper children. This policy is very familiar to today’s carers of looked after children, but was contested throughout the nineteenth century. This chapter sheds light onto how pauper children were perceived in local communities and whether affection or monetary gain was the motivation of foster parents. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that poor law central authorities began to favour boarding-out, primarily because of the loss of control over the children, and the often lax supervision by local boards of guardians. Chapter Four highlights what the 1834 poor law amendment act chiefly sought to change, the practice of allowing paupers a ‘dole’ in their own homes. Contrary to poor law propaganda, outdoor relief was never completely curtailed and was the principal strategy to relieve the majority of paupers outside London and certain ‘hard-line’ unions. Fewer sources exist through which to seek the lives of outdoor pauper children but I endeavour to read against the grain of sources about poverty in nineteenth-century England and Wales to uncover the children’s experiences. Although these policies were the most extensively used by many guardians, they are often neglected by historians because of the paucity of sources relating to them.

The final part of Pauper Children is devoted to the children who were sent to privately-run charitable institutions. Chapter Five explores diverse establishments, ‘orphan’ homes for Roman Catholic girls, many of which looked after physically or mentally disabled children. Unions also sent some boys to training ships to learn discipline and a trade, and these are the only institutions in the study to which a punitive label can be attached. Although disparate institutions, all were motivated by the making of respectable responsible subjects. The final chapter also examines disabled children, in this case those who were blind or deaf. It explores attitudes to the education of blind and deaf children and analyses the children’s lives and expectations and questions whether these institutions enabled or disabled the children in their care.

Davin claims that historians need ‘both zoom and wide angled lens’ to capture the particular as well as the general.53 Pauper Children offers a wide-ranging and multi-layered analysis of pauper children and their relationships with poverty, their parents and each other, the poor laws and philanthropy in England and Wales. The histories of pauper children are complicated by conflicting attitudes of (and within) regional poor law unions, competing strategies of child welfare activists and fluctuations in policy by central authorities.54 Although the ‘new’ poor law sought to bring uniformity to welfare provision, the treatment and care of pauper children was largely dependent on chance; where and with whom they lived. As Henriques claimed, many of the harsher elements of the poor laws were mitigated by the ‘goodwill’ of individual guardians, and this insight can also be ascribed to the behaviour of masters and matrons, house-mothers, teachers, and indeed the children’s own family, or to whom they were fostered.55 It is problematic to attempt to homogenise and pigeonhole the lives of pauper children, and the purpose of Pauper Children is not to offer generalised arguments. Their varied experiences are what matters. The lack of an overarching argument and conclusion need not be seen as an academic failure because they are elusive, but as an opportunity to explore in one book how the poor laws and philanthropy interacted with their dependent children, and how the children fared in a multiplicity of circumstances. The result is a more nuanced analysis that moves beyond Dickensian cliches of Victorian history to consider the multiple experiences of poor law children.

Part One: Pauper children and poor law institutions

‘As for exercise, it was nice cold weather, and he was allowed to perform his ablutions, every morning under the pump, in a stone yard, in the presence of Mr. Bumble, who prevented his catching cold, and caused a tingling sensation to pervade his frame, by repeated applications of the cane’.

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, Chapter three, 15.

Chapter One: ‘That bread! That greasy water!’56 The Workhouse

Early one morning in 1840s Staffordshire, a family left their cold and food-less home and walked a roundabout way, so as to avoid being seen, to Chell Workhouse in Stoke-on-Trent. Arriving at the ‘bastile’ they were assaulted by the sounds of doors banging, keys rattling, and the ‘metallic’ voices of workhouse staff who appeared to be ‘worked from within by hidden machinery’.57 Mother and father were separated from their children and each other, and the children were divided up according to gender and age, only to be reunited with their mother for an hour on Sundays.58 This would have been a familiar scenario to the thousands of men, women and children whose lives had reached the point where their parish workhouse was the only option left for them.

The word ‘workhouse’ still resonates with negative and uncomfortable meanings of a callous pre-welfare state past. Although few former workhouse inmates are still alive, their descendants (and their descendants) remember and disseminate their stories of revulsion. The hundred or so years of the operation of the ‘new’ poor laws was, and still largely is, embedded in popular imaginings as the system that spawned the workhouse. Contemporary critics and inmates likened the workhouse to a ‘Bastile’, a site devoid of pity and hope which generated an ‘unparalleled dread’.59 Defined as ‘poor-law prisons’ akin to ‘Dante’s Hell’,60 workhouses were emblems of grinding human manufactories loaded with gothic horror and homogeneity.

Perceptions of children and the workhouse have been further influenced by the enduring and poignant imagery of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Oliver, although a small fragile lad stepped forward from his place with other boys and dared to ask for more food. The boys of Dickens’ imaginings were held responsible for their poverty and dependence. However, in 1837 Assistant Poor Law Commissioner James Phillips Kay had claimed that pauper children maintained in workhouses were dependent ‘not as a consequence of their errors, but of their misfortunes’, subsequently children were one of the few groups of paupers to warrant widespread pity for their condition.61 Because of their association with pauper adults, it was felt that these children were not only ‘inefficiently trained’ but were ‘actually nurtured in vice’, and many of them would inevitably grow up to be ‘thieves or prostitutes or paupers’.62

As such, the workhouse was rarely imagined as a locus of normality for pauper children, and multiple alternative strategies were mooted by the central authorities.63 Many options were put forward to remove them from workhouses, and for those who remained, measures were put into place to counteract the perceived miasma of vice and idleness infiltrating the institutions. This was to be achieved via judiciously targeted education, discipline and training to negate the perceived moral contagion and hereditary pauperism within the workhouse. However, the rules laid down which were intended to avoid impulsive beatings of children and to protect them from contact with adults whom the authorities considered bad influences were perceived very differently by the children themselves. Delayed punishment in public was largely seen as a spectacle of cruelty and humiliation and classification as isolation and separation from family and friends. Initiatives such as these which sought to protect children and produce independent citizens were seen as harsh, but as Henriques claims the intentions were not ‘sadistic cruelty’ but they could be seen as insensitive.64

For those pauper children who were not boarded out, sent to other institutions or relieved at home with their families, the workhouse was their home, and before the 1870s, generally also their place of education. For these children their workhouse experience depended greatly upon luck; when they were in a workhouse, the characters of those in charge of them, and the vigilance and benevolence of local poor law guardians. Many, if not all children who found themselves in a workhouse had already experienced considerable trauma in their lives. Some were orphans whose both, or last surviving parent had recently died. As Murdoch has demonstrated, the categorisation of ‘orphan’ often obscured complex and fluid family frameworks in which a child could be left destitute by the death or desertion of one or both parents.65 ‘Orphans’, however their status was constructed, were always thought more malleable to reform and, because they were detached from stigmatised parents, they often generated more pity.66 However this pity did not always originate from the extended families of orphan children. Henry Morton Stanley’s two uncles refused to increase payment to the couple to whom he was fostered, so they left him at St Asaph workhouse in North Wales.67 Nonetheless, the future respectability and financial independence of the children was a huge motivating factor, so just because these policies also emulated what we today would recognise as ‘child-friendly’ principles which we equate with benevolence, it must not be forgotten that policies of goodwill and strategies of control were, and still often are, interrelated.68

Separation

Classification was central to the premise of the workhouse system.69 This meant separation of families because of what the central authorities perceived as the moral dangers endemic in unsegregated accommodation where children were forced to live with ‘the very refuse of the population’.70 Allusions to the amoral behaviour of animals accompanied rhetoric concerning the chaotic living conditions of the poor, described by a London Medical Officer as ‘swarms by whom delicacy and decency in their social relations are quite unconceived’.71 Thus, juvenile delinquency was perceived as a natural consequence of overcrowded poverty and ‘street life’.72 However, some of the most strident criticism of the ‘new’ poor law has been levied at the forced separation and subsequent compartmentalisation of pauper families in workhouses.

James Kay had claimed that separation of children from adult paupers was essential, but ‘no objection’ was made to parents seeing their children during the day and at meals.73 However, it is unclear how much conversation or physical interaction took place between parent and child. There are records of mothers looking after their sick children in the workhouse, and contact can also be demonstrated by the actions of women like Mary Richards who was punished for insubordination regarding her comments when her children were disciplined for damaging the workhouse. Although power to punish remained with the workhouse management, Richards’ vocal resistance diminished the effects of segregation by confirming her maternal protection.74 As Hopkins claims, families were no more broken up by the ‘new’ poor law than the ‘old’, given that the average stay in the workhouse was less than three months for the majority of children.75

The Cambrian newspaper had regarded the ‘clamour’ concerning forced separation raised by ‘pseudo-philanthropists’ as misdirected. It took the view that poverty and overcrowding were inevitable triggers of corruption, and when these poor families occupied the same room the result was ‘the most disgusting indecency and vice’. Although the newspaper also reiterated the Poor Law Commissioners that temporary separation was a condition endured in many households, such as army and navy families, it failed to recognise that children of military families were not always parted from their mothers as well as their fathers.76 However, many children of the middle and upper classes were routinely separated from their parents in boarding-schools for long periods of time. Thus the middle-class pattern of child-parent educational separation was transferred to the pauper class. Confirming the benefits of this regime, James Kay claimed for ‘temporary separation for the permanent advantage of the children, similar to that which occurs in all ranks’.77

Some families also separated themselves. One mother ‘willingly assented to the separation for the benefit of her children learning they received’ in the workhouse.78 Nora Adnam’s father left them, with the collusion of her mother, when he was unable to work after injuring his arm and wrist so mother and children would be accepted in the workhouse. Joseph Bell’s sister took him to Bedford Workhouse, where she left him ‘looking fondly on me as a mother looking at their child for the last time’.79 In the multiple questionnaires poor law unions completed for the central authorities, the term ‘orphan’ was often explained as ‘having lost one or both parents’, and indeed some parents left one or more children in the workhouse while they attempted to establish a stable occupation and home. This could involve negotiating with the union and illustrates again how adult workhouse inmates were not always powerless to control their own lives. Such was the case of Sarah Williams who, in 1837, was described as a workhouse inmate with ‘twin bastard children’. She wanted to leave the workhouse with one of her children who she would maintain herself, if the parish looked after the other child.80

While poor law ideology may have separated the children from morally infectious adults, children were bundled together themselves, albeit separated by gender and sometimes age. Boys especially were subjected to abuse and bullying from their peers who had likely been poorly treated themselves. Bell talks about the ‘nicer’ boys being willing to make friends while the ‘courser’ boys, who made up the majority, made things ‘uncomfortable’ for him. Bell later countered one ‘great hulk of a boy’ by successfully beating him in a fight, which made him a favourite with the other boys, and they chose him as ‘captain’ in games of football.81 There exist many stories of ‘timid’ boys who ‘shrank from the bestialities and obscenities’ of their peers were forced to share bedrooms with those who Shaw called the ‘children of the devil’.82

Education

In his 1836 report to the Poor Law Commission, Edward Tufnell had felt that the improvements in the care of pauper children following the 1834 act was one of the ‘most pleasing and popular’ results of the new legislation. In his opinion, workhouse children now enjoyed ‘advantages of instruction’ that were unlikely to be provided by ‘improvident parents’.83 Although many workhouse children, especially in the decades prior to the 1870s, probably received a better education than many children living at home in poor families, this can be also be attributed to some parents finding even ‘the school pence’ beyond their means rather than a lack of care and prudence, although there is evidence of outdoor pauper families paying for their children to attend schools.84

In a later report, Tufnell reiterated his unequivocal view that it was ‘impossible to over-estimate the importance’ of the education of pauper children.85 Of specific significance was the value of education as a tool for checking future welfare dependency and ingrained immoral tendencies which were thought to be consequential of pauperism. This was also thought by James Phillips Kay, who as Poor Law Commissioner since 1835 and Secretary to the Committee of Council on Education until 1849, was a leading authority on both pauperism and education and was credited with initiating a ‘social revolution’ in the field of education.86 Kay felt that education was one of the most important ways of ‘eradicating the germs of pauperism from the rising generation’; however, it must be remembered that Kay’s ideas were considered extremely radical by many, and Digby and Searby claim that he also showed a tendency to ‘sentimentalise’ children.87 Nevertheless, in 1861, the exhaustive Newcastle Commission inquiry into popular education spoke about ‘educating children out of their vicious propensities’.88 Similarly, in 1844 J. H. Vivian, Member of Parliament for Swansea, thought that pauper children should not only be ‘sufficiently instructed’, but proper attention ought to be paid to their ‘morals and conduct’, so they would become ‘independent and respectable members of society’.89 Joseph Bell appears to have a bright boy who answered his teachers’ queries with ease, unlike the other boys in the class who looked ‘simple and perplexed’ at what Bell saw as a very easy question. He was later made senior head boy of the institution.90

Crowther claims that workhouse officers were ‘selected at worst through nepotism, at best because they were honest’.91 She calculated from figures taken from a Poor Law Return that the average salary paid to workhouse school mistresses in 1849 was £16 a year. Some unions, such as those in East Anglia, paid up to £20 a year.92 From 1846 unions could claim monetary grants for education from the central authorities. The amount depended upon the skill level of the teacher and the numbers of children being taught.93 On average, in I852, first-class masters in common elementary schools earned £133 a year while the equivalent workhouse master was earning £65.94

However, economic pragmatism also came to the fore at times. Pauper inmates were often used for teaching, such as at Tenbury wells in Worcestershire.95 In Swansea workhouse, when the school mistress was dismissed because of low numbers, six older girls were taught by the school master, and the younger girls were in the charge of an inmate, Ellen Crone.96 Jelinger Symons did not appear too unhappy by this makeshift strategy as three months earlier he had recommended that Crone should be given ‘a small sum’ for teaching the girls reading and needlework, although he took the opportunity again to recommend the formation of a district school with neighbouring unions.97 In 1847 the infamous inquiry known in Wales as the Brad y Llyfrau Gleision or the ‘treachery of the Blue Books’ was published and later described by one historian as ‘the Glencoe and Amritsar of Welsh history’.98 The inquiry concluded that the Welsh were badly educated, poor, dirty and unchaste. Use of the Welsh language was blamed for the alleged ‘backwardness’ of the Welsh, and one of the consequences of the report was the imposition of a wholly English system of education in Wales.99

Punishments

In 1841 James Phillip Kay had recommended that ‘once the children had been trained into docility’ corporal punishment should ‘fall into disuse’ as soon as possible.100 Later in the century the Reverend Rudge, chaplain of the North Surrey District School, claimed that because of ‘gentle persuasion’ and ‘the practice of private prayer’, corporal punishment was becoming ‘almost unknown’ in the school.101 However, a Poor Law Report of 1873 had detailed the corporal punishment of boys in workhouse across Britain during a six month period.102 The vast majority of unions across Britain recorded little or no corporal punishment during this period, however there were some exceptions. In Birmingham, 19 children were beaten; the Isle of Wight and Oswestry recorded 12 and 10 punishments respectively. Unions within London recorded some of the highest figures with 15 in St. Pancras, 16 in Marylebone and 38 in Shoreditch. In Wales, only the Anglesey Union had inflicted a substantial number of corporal punishments at eight. Every other union had reported no corporal punishment except one by either the Merthyr or Neath Union.103 The large district schools of Walsall and West Bromwich recorded the highest overall number of punishments at 69.104 However, former inmates’ memories show that corporal punishment was always remembered and happened more frequently than the ‘official’ records suggest. Shaw talks about how boys’ reactions to beating varied considerably. Some boys would ‘writhe and sob’, while others maintained a ‘stolid silence’. One beating appears to be lodged firm in Shaw’s memory; he reported that it was a ‘living horror’, and during the beating he witnessed, ‘thin red stripes’ appeared over the boy’s back, with the ‘screaming’ dying down as the boy lost consciousness.105

Whilst the ‘new’ poor law generated a vast bureaucratic record-keeping machine it is prudent to assume incompleteness within most poor law records, and the incidence of corporal punishment is one area where interrogation of the available sources is particularly advisable. It is, however, unlikely that any firm conclusions can be made regarding the over or under reporting of corporal punishment. Neither is it prudent to forward unsubstantiated generalisations such as Hendrick’s argument that the prevalence of ‘legal violence’ in institutions ‘nearly always’ resulted in not only corporal punishment, but also sexual abuse.106 It is therefore problematic to attempt firm assumptions concerning the punishment of pauper children because, as Crowther claims, ‘amongst all classes of society, treatment of children ranged from the utmost severity to total refusal to inflict punishment’.107 Similarly, Symons recorded that in workhouse schools he had encountered ‘every diversity of schoolteacher from very nearly the best, to decidedly the worst.108 Although a lack of uniformity existed regarding the disciplining of pauper children prior to an order of 1841, the pulling or ‘clipping’ of ears as a punishment survived long into the twentieth century, if largely anecdotally.109 Although it is likely that a degree of under-reporting of punishment abuses occurred, Crompton’s assertion that cases of over-punishment ‘almost always’ went unrecorded is impossible to substantiate and, as Murdoch demonstrates, complaints were initiated from within institutions and also from parents.110

However, memories of corporal punishment always stay with former pauper children. Joseph Bell remembers the day when he was punished for writing and delivering a letter to his friend Mary, who was also in the institution. While she suffered the humiliation and distress of having her hair cut off as older girls were allowed to have their hair long, and Mary was very proud of hers, Joseph suffered pain as well as humiliation.111 He was taken into a public room, and as he had been on short rations for a fortnight was ‘skin and bones’ when he was told to remove all his clothes ready for his punishment. Then he recalled ‘five burly, red faced, jolly looking farmers’ entered the room’, they were ‘laughing as though they were about to enjoy the fun, as if they were going to witness a prize fight or a Spanish bull fight’.112 Once the beating began he recalled that ‘as each stroke descended the pain grew more intense, the weals started quivering and running into each other, and felt like a dreadful burning sensation’. After the twelfth blow he fell on the floor ‘like a dead thing’. Physical pain and injury was not the only result of the beating, he later became ‘very depressed and lost interest in everything’.113 Joseph bell had previously thought of his masters with respect and sometimes affection, and it must have come as a huge shock to be treated so by them, even if some had tried to reduce the punishment he received. That the central authorities did not necessarily equate authority with cruelty had been confirmed in an 1841 report which advised that care should be taken in the selection of school master ‘lest we introduce a tyrannical despot rather than a father’.114 Jelinger Symons did not believe that ‘cruelty or severity of discipline’ was common in workhouse schools, although he did feel they existed in some unions.115

Health

In Cardiff Workhouse, an enquiry into infant mortality in 1854 showed that out of 114 babies born in the workhouse in the three years prior to June 1854, 39 had died before their second birthday, however, the medical officer blamed these high figures on a measles epidemic.116 Contagious skin and eye diseases appeared to be prevalent among the workhouse children. Instances of the itch (scabies) especially and scald head (ringworm) were mentioned repeatedly in the sources, as were general eye complaints and the more serious ophthalmia, which was a major cause of childhood blindness in the nineteenth century.117 It was agreed by guardians in the 1850s that the appearance of the children was one of pallor and sickliness. One Swansea guardian, Matthew Moggridge, was particularly anxious about this and remarked that a workhouse boy could always be picked out of a crowd because of his ‘sickly appearance’, which was at odds with the ‘erect and manly gait’ which had been expected by the Poor Law Commission in 1841.118 However, contemporary commentators frequently bemoaned what Florence Hill termed ‘the inevitable consequences of ordinary workhouse life’. For Hill, this equated to a ‘dulness [sic] of apprehension, ill-temper, a want of self-respect, and negligence as regards the care of property’.119 Charles Dickens claimed that the ‘monotonous semi-prison life’ of the workhouse must ‘degrade and depress’ the minds of pauper children.120 In Swansea John Dillwyn Llewelyn described the workhouse children thus:

They rise in the morning, are dressed by the nurse in the livery of pauperism - the grey jacket and hood, that marks them as a peculiar and inferior class; the bell rings, and the breakfast appears; dinner comes round for them with equal regularity; then there is the weary round of lessons to be learnt; a poor attempt to play in a court-yard, not so good as the airing yards in a gaol; a life of listless idleness; a depressing routine not calculated to elevate the moral or physical condition of a boy or girl; a system of continual dependence upon the help and assistance of others, which must tend to perpetuate a race of paupers.121

Nonetheless, many of these assertions were preludes to pushing for personal agendas in the care of pauper children. In the case of Hill, Dickens and Dillwyn Llewelyn above, it was their championing of the boarding-out system.122 Philanthropist Francis Peek vocalised Dillwyn Llewelyn’s concerns more directly when he contended that workhouse children were ‘lamentably deficient in that spirit of independence which is the greatest stimulus to exertion’.123 In 1855 guardians had discussed the ‘evils resulting’ from the system of sick children sharing a ward with prostitutes suffering from venereal and other ‘loathsome diseases’. One visitor was shocked to find a sick female child in the same bed as a ‘well known prostitute’. It was considered that this state of affairs could only lead to the girls in the workhouse becoming prostitutes themselves and is emblematic of the perception that ‘vicious’ characteristics such as immorality were contagious.124 This assessment of workhouses as ‘promiscuous environments’ was widespread, and the premise was reiterated by social purity campaigner Ellice Hopkins, who claimed that girls in the workhouse faced the threat of ‘the deepest degradation of all’.125 It is likely that the workhouse infirmary was the only treatment centre available for poor women with venereal disease and their presence was thought liable to contaminate the vulnerable morals of young girls. Certain voluntary hospitals served the non-pauper working-class while, as Walkowitz claims, the ‘less desirable patients’ used the workhouse infirmary.126

Although it is of course appropriate that the guardians should want to protect young female inmates from the perceived dangers of moral contagion, were they manipulated by what Driver calls the ‘discourse of moral regulation’ and, were young girls so influenced by their association with the alleged ‘vicious’ characteristics of some inmates that complete separation was imperative?127 Florence Hill was ‘convinced’ that the inevitable association between girls and mothers of illegitimate children in workhouses was ‘polluting’ and she cited the similar views of many others, including Edward Tufnell, Edward Senior and Jelinger Symons, as corroboration.128 Symons had claimed that even when the children were in separate rooms from the other workhouse inmates, they could hear continually the ‘obscene conversation of the depraved portion of the adults’.129 This expectation continued into the twentieth century. As Thane points out, although the 1905-9 Poor Laws Royal Commission found little evidence, it was still assumed that workhouses contained a large number of prostitutes.130 However, although Andrew Doyle was a long-standing advocate of separate district schools for pauper children, he derided the argument that a child would become ‘contaminated’ by their occasional association with adults in the workhouse ‘as it would contract disease if it entered a plague-stricken city’.131 Similarly in London, arguably containing the most overcrowded workhouses, a direct correlation between a workhouse childhood and adult criminality was not borne out. The vast majority of women under 40 years of age who were incarcerated in Metropolitan prisons on 9 April 1873 had not been educated in workhouse schools.132

Diet

One of the more enduring images in Oliver Twist, which was probably confirmed and disseminated more widely by the 1968 film Oliver! is the apparent near-starvation suffered by workhouse children. Dickens wrote that ‘boys have generally excellent appetites’ which the workhouse failed to satisfy with ‘three meals of thin gruel a-day, with an onion twice a week, and half a roll on Sundays.133 This potent imagery appears to have coloured some historians’ view of workhouse diets. Crompton’s assertion that an already ‘inadequate’ diet was aggravated by ‘institutionalised starving’ as punishment, is one example.134 In her extensive analysis of 3,000 workhouse and prison diets, Johnston claims that ‘starvation had no role in the policies of either institution’.135 It is very likely that workhouse children were better fed than their contemporaries living at home with poor parents. Of course, it could be claimed that the diet was still ‘inadequate’ by today’s benchmarks, but similar anachronistic comparisons could be made concerning most social conditions of the nineteenth century and is not helpful to our understanding of the period.136

In the workhouse, children were assured of receiving a fixed amount of food and did not have to compete for food with the adults and siblings in their family.137 As Ross claims, death by starvation was still a ‘regular occurrence’ up to and after 1870.138 Food was also used as a means of control and punishments often took the form of a modification of rations. This appears to be generally the substitution of one meal for bread and water or in the case of many girls, a dinner of potatoes instead of the day’s predetermined food.139 Four young girls who had damaged a partition in the workhouse were punished by their dinner allowance being halved and their treacle ration withdrawn.140 Workhouse food was monotonous, under-seasoned and probably badly cooked, but the quantities were sufficient and it was designed to deter rather than starve.141 As Edward Ostler, one time medical officer to Swansea House of Industry, reported to the 1834 Royal Commission, ‘humanity dictates that the inmates of a workhouse should be fed quite as well as a labourer’s family’, and the food, whilst wholesome, should be ‘of the plainest description’. Ostler described the pre-1834 diet in Swansea workhouse as meat, broth and pea soup, each for two days, with fish on the seventh day. No amounts were given, but Ostler also reported that the diet should be ‘sufficient’.142

Food was also used as reward as well as punishment. Various treats were given to the children throughout the year and most included food that could be considered an indulgence. These treats were promoted as being obtained by good behaviour and by conforming to the projected ethos of work, independence and thrift as adults. One annual trip to a local beach also saw the children ‘plentifully regaled with tea and plumcake’ and special teas were often arranged.143 Christmas was a time that appears to be most associated with ‘luxury’ food for workhouse children. Entertainment too was always a feature in workhouse Christmas celebrations. Festivities in 1882 were referred to as ‘a right merrie day’ and a newspaper reported that ‘the remarkable feature in the programme was the difference in the ages of the musicians. The youngest being 3, sang ‘a little cock sparrow who sat in a tree’, the oldest was ‘a sprightly young fellow of 83’, the day ended with the ‘grateful’ inmates going to their wards ‘feeling thankful that in the general joy they were not forgotten’.144 Joseph Bell remembered Christmas with fondness, and he too enjoyed the beef and plum pudding served to the children who were also allowed second helpings. The men of the workhouse were given beer and tobacco, while the women enjoyed snuff and tea. Before the children were sent to bed to dream about the Christmas tree celebrations the following day, they were all given a ‘little present’ from the visitors.145

In some unions however, poor diets generated widely reported scandals. At Andover workhouse the diet was found to be extremely meagre in quantity, resulting partly from the ‘dishonesty’ of the workhouse master. In consequence, inmates who were employed in bone crushing ‘ate the gristle and marrow of the bones they were set to break’. The subsequent inquiry also found that if the workhouse visiting committee had ‘acted regularly and duly in the discharge of their important duties’, the scandals could not have occurred.146

Conclusions

A weary statement by schools inspector, J. L. Clutterbuck paints a rather jaded and monotonous picture of workhouse education:

The annals of workhouse schools, as a rule, are uneventful. Teachers come and go, and boards of guardians introduce, from time to time, certain changes of detail or administration; but the same general features are observable from year to year.147

This description of the workhouse school can be extended to the life of a workhouse child, dreary, monotonous and probably lacking stimulus. However, for all its reputation as a locus of discipline and disgrace, the workhouse was also a site of future redemption.148 Workhouses may have been regarded with horror by some, but it was nearly always imagined by the poor law guardians as a place of reclamation for the children in their care. Combined strategies of moral and intellectual education and religious and vocational training of workhouse children were intended to inculcate respectability, responsibility and independence. Children were trained to conform to notions of what was imagined as normal working-class uprightness and industry. Their education would lift them out of pauperism and their proscribed leisure time and ‘treats’ would generate expectations which could be achieved by their hard work and decency. However, the children’s proximity to the more ‘vicious’ inmates of the workhouse was imagined to instil beliefs that a similar lifestyle could be acquired by means of prostitution or criminality. Poor law guardians believed that their objective for fashioning pauper children into industrious citizens of the future would not be achieved in the workhouse. Consequently, the following chapters analyse the multiple strategies used by guardians and central authorities to realise their aims.

Chapter Two: ‘Thousands of children to mend’.149 Beyond the workhouse

James Andrews was seven years old when he died of cholera in January 1849. On his final journey to hospital he sat on the knee of a 14 year old classmate and took some comfort from laying his head on the older boy’s shoulder. His body was so thin that the doctor who performed his autopsy remarked on its startling emaciation.150 James was survived by his older brother who had also lived in the same pauper ‘farm’ in Tooting which was owned by George Drouet. James Andrews was one of around 180 children to die of cholera in Drouet’s school that January, and one of the 1,400 pauper children Drouet had reportedly underfed and mistreated. Twelve year old Thomas Mills had run away twice from the school because of hunger and beatings; the children were often thirsty and the boys took to drinking water that ran down a gutter from the girls’ bathroom. Punishments other than severe beatings included head shaving, having clothes taken away, and boys being made to wear girls’ clothes in school.151

The conditions in Drouet’s school were reported across Britain at the time, and were often cited many years later as a cautionary tale regarding the care of their pauper children. An article in the Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian reprinted from the Cheltenham Journal was similar to many others across Britain when it asked how the poor law and the people of London could ‘coop up and starve 1,400 children’.152 Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper called Drouet’s a ‘pest house’ and blamed guardians for ‘atrocities that can never be perpetrated again’.153 Charles Dickens wrote several articles anonymously in The Examiner about the tragedy, and his anger is palpable. He claimed that cholera was present in Drouet’s establishment because ‘it was brutally conducted, vilely kept, preposterously inspected, dishonestly defended, a disgrace to a Christian community, and a stain upon a civilised land’.154 Scandals and crises often drove change in both local and central poor law strategy throughout the nineteenth century; the tragedy at Drouet’s had a profound and long-term impact on future policies and perceptions of separate establishments for pauper children.

This chapter argues that strategies concerning institutions and homes for pauper children away from the workhouse shifted considerably during the second half of the nineteenth century and into the Edwardian period. Most changes were contested, and they generated fierce debate and argument among poor law officials, the press and child welfare campaigners.155 Analysis of these debates and policies allows us glimpses into the lived experiences of pauper children, and enhances our understanding of how the well-being and future prospects of poor children in England and Wales were perceived. Pauper children were seen as being damaged by their parentage, surroundings or time spent in the workhouse. They were broken children who, as Dickens claimed, needed to be mended.156 Solutions and motives for the children’s restoration were driven by overlapping and competing factors of concern, duty and anxiety. The intentions and ideologies of many poor law officials and commentators were altruistic and driven by notions of pity, compassion and Christian duty for vulnerable children. However, fear of the children’s possible lifelong dependency on the poor laws powered campaigns for costly education and training that could only be provided away from the workhouse at separate establishments.

Depending on the fashions of the time, geographical location or guardians’ will, a pauper child could find themselves living in a ‘farm’ school like that at Quatt in Shropshire or in vast buildings such as the district schools built for the Manchester and Liverpool poor law unions; the establishment of the equally large North Surrey District School was an explicit response to the tragedy at Drouet’s school. Other separate establishments also sought to remove children away from urban centres but were based on a ‘village’ concept containing houses, shops, schools and training facilities. Later in the nineteenth century smaller ‘cottage homes’ were established which were not so insular and where children attended the local village schools. By the beginning of the twentieth century many unions had followed Sheffield Union’s ‘scattered homes’ system where small groups of children lived in in ordinary houses in the community with a foster mother. While at first glance this appears to be a rather whiggish progression from ‘barrack schools’ to the localised foster care favoured for looked-after children today, many of these strategies overlapped and, like today, policies dipped in and out of favour and fashion and were keenly promoted by their supporters, and criticised by their detractors.

District Schools

No one strategy was fully embraced by all stakeholders and poor law officials. However, the close geographical proximity between London poor law unions, and the shadow cast by Drouet meant there was little difficulty to their joining forces and over 3,000 places for London children were created in the subsequent district schools in the ten years to 1857.157 While legislation in 1844 and 1848 had enabled poor law unions to join forces in order to form large school districts as a means of removing children from workhouses, many London unions had ‘farmed out’ children prior to this because of severe workhouse overcrowding in London.158 While several smaller private providers had offered places for children from London unions in Edmonton and Enfield, the child ‘farming’ business had been dominated by the aforementioned George Drouet in Brixton and later in Tooting, and another large scale contractor Frederick Aubin in Norwood.159 While Drouet’s farm became an allegory for the neglect of pauper children, improvements brought about as a result of critical reports in the 1840s had culminated in the poor law authority buying Frederick Aubin’s school in Norwood, rebranding it the Central London District School and retaining him as manager.160

The publicity given to the opening of the first purpose-built poor law district school, the North Surrey District School, demonstrates that pauper children remained in the public domain, and their treatment was subjected to scrutiny from many quarters. The establishment of large district and separate schools was celebrated as an innovation in child welfare. Among the guests at the opening ceremony were the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishops of London and Winchester, the High Sheriff of Surrey, two local members of Parliament and a ‘large assemblage’ of magistrates. While around 200 eminent guests enjoyed a meal provided by a local tavern, over 400 children were ‘regaled with roast beef and plum pudding’.161 Nonetheless, more simple fare was also popular with the children such as bread and milk cooked until crisp in the oven.162

The significant sums of public money spent building and equipping district schools also suggests that the care and education of pauper children was of considerable importance to poor law policy-makers. Just under £50,000 was spent purchasing the Norwood school from Frederick Aubin, furnishing it and later relocating the establishment to new premises at Hanwell.163 Similarly, the North Surrey School cost over £31,000 and the South Metropolitan over £43,000.164 This expenditure did not go unremarked and led to the district school for the Manchester union at Swinton being dubbed a ‘pauper palace’ because of its architecture and facilities.165 Dickens described Swinton as easily mistaken for a ‘wealthy nobleman’s residence’ with a frontage of 450 feet, surrounded by ‘pleasure-gardens and play-grounds’, along with cultivated land totalling around 22 acres. It must have presented an awe-inspiring sight to boys and girls from the streets or lodging houses of Manchester and the overcrowded workhouses of Liverpool.166

While many of the children would have been used to the size and forbidding nature of the ‘bastille’ type workhouses of urban England, they must have been astonished by the buildings and expanse of land in which the schools were set. On his first day at The South Metropolitan School at Sutton, ‘WHR’ remembered his first train journey to the schools, and how he had walked up the hill from the railway station hand in hand with a friend gazing up at the ‘magnificent place’.167 He was ‘fairly wild with delight, the place seemed so big’ and the playground a ‘fine large yard’. Edward Balne attended the Central London District Schools in Hanwell, Middlesex and he also spoke rather longingly about the space and situation at Hanwell which included ‘a wonderful view of spacious playing fields, country lanes, extensive farmlands […] fruit trees, a well-kept cricket ground and a football pitch’.168

While for the children the space signified a perceived release from cramped conditions of workhouse or home, the authorities saw the space and facilities offered by schools away from the workhouse as a means to compartmentalise and classify the children and their lives. As Murdoch claims, the ‘organisation of space’ within institutions followed doctrines of middle-class domesticity which were embraced by poor law establishments, and was seen as the polar opposite to what were perceived as the chaotic and undomesticated homes of the poor.169 Districts schools offered the space to provide segregation of work and recreation as well as gender and age compartmentalisations; they appeared a world away from the cramped and morally confused workhouses. Assistant Poor Law Commissioner Edward Tufnell remarked on the importance of siting schools at a distance from a town for the physical and moral health of the children.170 Many commentators perceived the rural space as a domestic ideal, Dickens talked of schools being ‘far away’ from ‘the cloud of smoke’ with a ‘succession of charming views’.171 Writers of domesticity often perceived children metaphorically as gardens, because of the need to sow and cultivate morality, while guarding against ‘the winds of adversity and the weeds of vice’.172 While children spoke of spaces in which to ‘romp’; stakeholders regarded rural space as free of miasma, with fresh wind to blow the ‘bad’ air away.173 One Welsh poor law guardian differentiated the urban centre of Swansea and its rural outskirts as respectively the ‘black country’ and the ‘green country’.174

The education offered children in district schools was superior to that which most independent labourers could afford for their own children. An 1845 report by Seymour Tremenheere and Edward Tufnell gives us some insight into the education and daily lives of the children in Aubin’s establishment at Norwood which housed between 800 and 1,100 children under 15.175 The curriculum was designed to produce able and employable citizens, and, apart from a lack of the classics, the establishment appears not dissimilar to a middle-class boarding school. Subjects studied here were common to most district schools and included the Bible and scripture history, tables, geography, reading and writing, arithmetic and dictation. Cultural pursuits such as drawing and music were also offered and taken up. The facilities for vocational training offered the boys was purely artisanal and included a tailors shop and cobblers as well as a blacksmith’s forge. Marching drill and a naval class included climbing ships’ rigging over which, Dickens related, the boys swarmed ‘with great delight’.176

The popularity of a lending library with the older boys at Norwood demonstrates that reading for pleasure was an acceptable activity, although doubtless the content would have been monitored closely. The inspectors reported that the ‘discipline and moral tone’ of the school had been raised after masters gave more of their time ‘during the hours of relaxation’. This included evening walks, and on winter and spring evenings an ‘evening school’ was established, and boys were also responsible for their own garden plots in the summer months.177 These activities followed patterns of class-appropriate and ‘civilising’ activities which were perceived as crucial to the future respectability and employability of undomesticated and abandoned children.178 Some children like Olive Jewry and Alfred City had backgrounds so unknowable they were named after the only features that could be discerned about them.179

These huge district schools, often with over a thousand children in one establishment, justified the expense involved in providing the wide range of educational and vocational activities for the children. At Norwood, the educational progress of the 430 boys appears to be generally satisfactory with some achievements and some failures in the tests they were set. Their day was organised into lessons between 8.30 and 11.30, and 1.30 and 4.30 as well as a 15 minute break morning and afternoon. The boys (like the girls) had supper at 6.00pm and went to bed at 9.00pm.180 In the North Surrey school many different skills were taught. 84 children learned about agriculture, 4 baking, 40 shoemaking, 26 tailoring, 8 carpentry, 6 painting, and 26 were taught general household duties. Some boys were taught engineering and plumbing as there were two steam engines on the premises.181

Household duties were routinely taught to the girls, with the gendered expectations of the day determining how pauper children were educated and trained at district schools, although Jane Senior felt that ‘more mothering’ was lacking from most girls’ educations.182 While girls generally studied similar academic subjects as boys, it was thought that ‘the same amount of intellectual development’ was not as necessary for the ‘female sex as to the male sex’. Girls’ educational abilities were also not praised as much as boys although failures in girls’ understanding was often pointed out.183 Tufnell reported that girls benefitted from the district schools but apart from a few who trained as pupil teachers, most invariably became domestic servants. Tufnell felt that ‘the inevitably dull routine of such a life’ deprived ‘their histories of that varied romantic character which often distinguishes the life of a boy pushing his way in the word, and hence their biographies are never so interesting or quotable’.184

Commentators such as Dickens also wrote far less about the girls in Norwood, saying only that they had three days of schooling and three days of training in ‘household’ occupations’ such as cleaning, washing ironing, mangling and needlework’.185 Although these tasks were thought appropriate and ‘natural’ for girls, many hated sewing and darning. The Kirkham home had ‘darning nights’, and one girl related ‘how we hated this’. When clothes were returned clean from the laundry buttons had to be sewed on and stockings mended, if the house mother wasn’t satisfied she would put a scissors through the darn and it had to be done again.186

This training was designed to produce literate and numerate wives and servants, and girls from Norwood apparently found and kept places in domestic service and were generally reported as giving satisfaction to their employers.187 As in the workhouse, there was strict segregation of the sexes. In Hanwell, Edward Balne remembered that in 12 years he never entered the girls’ grounds and never spoke at meals to them apart from the annual summer fete.188 In the Ely Industrial Schools of the Cardiff Union, children were segregated during school hours but at meal times met ‘in one common room as a family should do’.189

As district schools contained huge numbers of children, discipline would have been vital to the school’s curriculum, and while undeniably essential in such a large establishment, some of the methods seem uncomfortably manipulative. In Swinton, the training regime required children to resist temptations and distractions. The junior playground was lined on two sides by currant bushes, and if any of the fruit was taken by children prematurely they were left out of the subsequent picking and eating of the ripe fruits. Similarly, the children were expected to ignore the attentions of the master’s friendly dog who was allowed to roam freely among them and instead concentrate solely on their lessons.190 Tufnell reported that in the first week of the North Surrey school many children rioted and caused £100 worth of damage, however, they had quickly become ‘so perfectly quiet and orderly’ that he compared their lack of riotous conduct to a flock of sheep.191 That children were trained to be ‘perfectly quiet’ would form much of the later criticism levelled at large ‘barrack’ schools. Poor law guardian for Eastbourne, Wilhelmina Brodie Hall described the district school child as having no means of doing anything that it likes; it has to do everything by rule, and becomes a mere machine’.192 Edward Balne seemed to revel in the military lifestyle: ‘up at 5.30 ‘reveille’, he recorded, followed by some domestic duties supervised by a servant and two boy ‘corporals’, then the boys were ‘fell in’ for breakfast at 7.30.193 Balne later became a soldier, so whether his schooling led to this career choice or his language for the school was directed by his future career is uncertain.

Wales