Ted’s Numbers

M. Norton Wise, Mary S. Morgan, Emmanuel Didier, Lorraine Daston and Soraya de Chadarevian

Rounded Globe

Rounded Globe

Contents

- Preface

- Ken Alder INTRODUCING TED

- Margo Anderson ENCOUNTERING TED

- Fabrice Bardet STATISTICS AND ACCOUNTING(S), A MATTER OF COLLECTIVE TRUST, AND VICE VERSA

- Jean-Pierre Beaud & Jean-Guy Prévost TRUST IN PORTER

- Luc Berlivet KNOWLEDGEABLE BUREAUCRACIES

- Dan Bouk COUNT ME

- Bruce G. Carruthers ON THE INEFFABLE TED-NESS OF TED

- John Carson SOME WORDS AND PICTURES APPRECIATING TED AND HIS NUMBERS

- Karine Chemla TRUST IN Π

- Roser Cussó THE MYSTERY LIVES ON

- Lorraine Daston THE VOICE OF TED

- Soraya de Chadarevian MORE THAN JUST ABOUT NUMBERS

- Emmanuel Didier TED’S PERSPECTIVES

- Wendy Espeland FACTS and ODE TO TED

- Gerd Gigerenzer ALL IN THE NUMBERS

- Sarah E. Igo FUNNY HISTORIANS

- Morgane Labbé AT THE BORDER

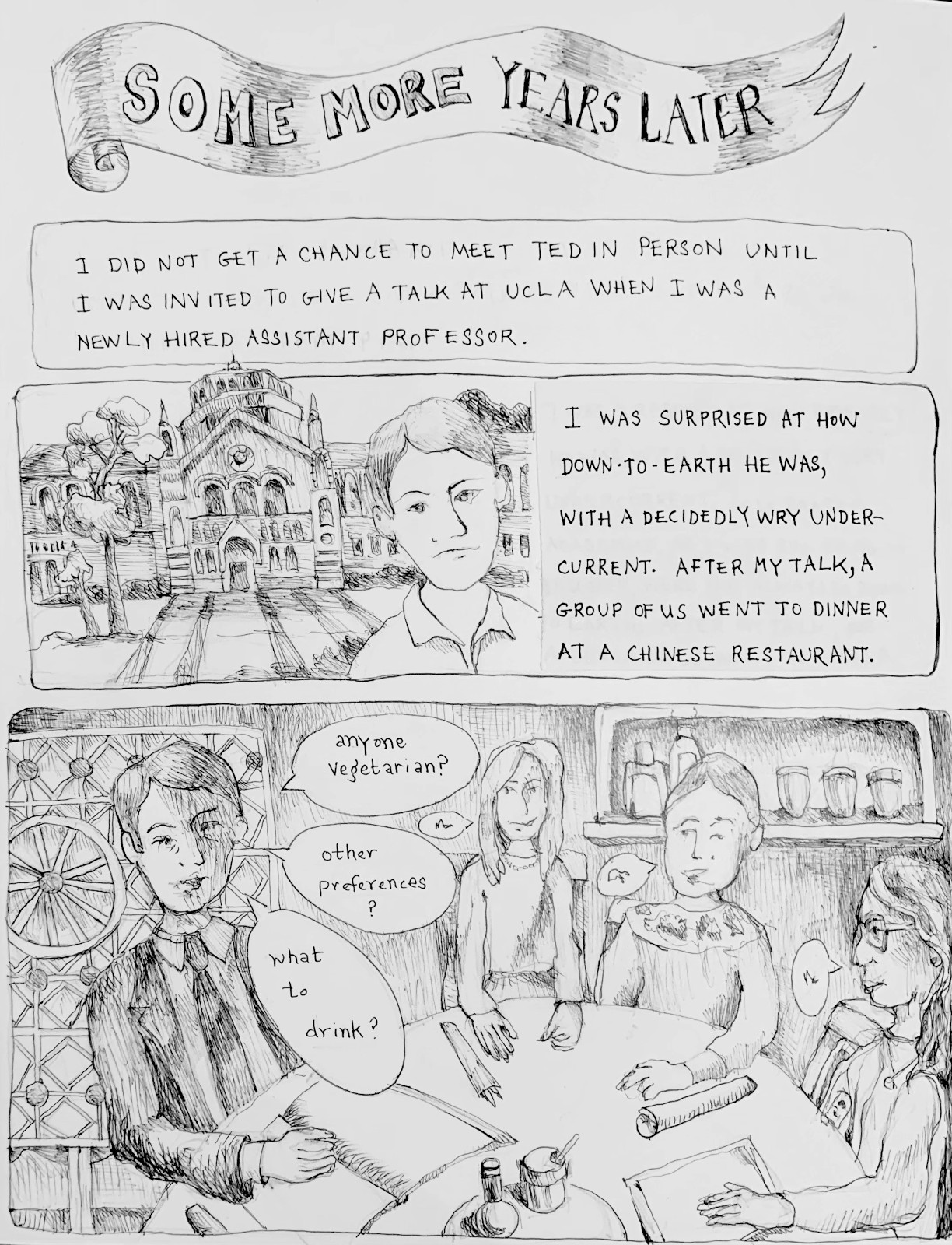

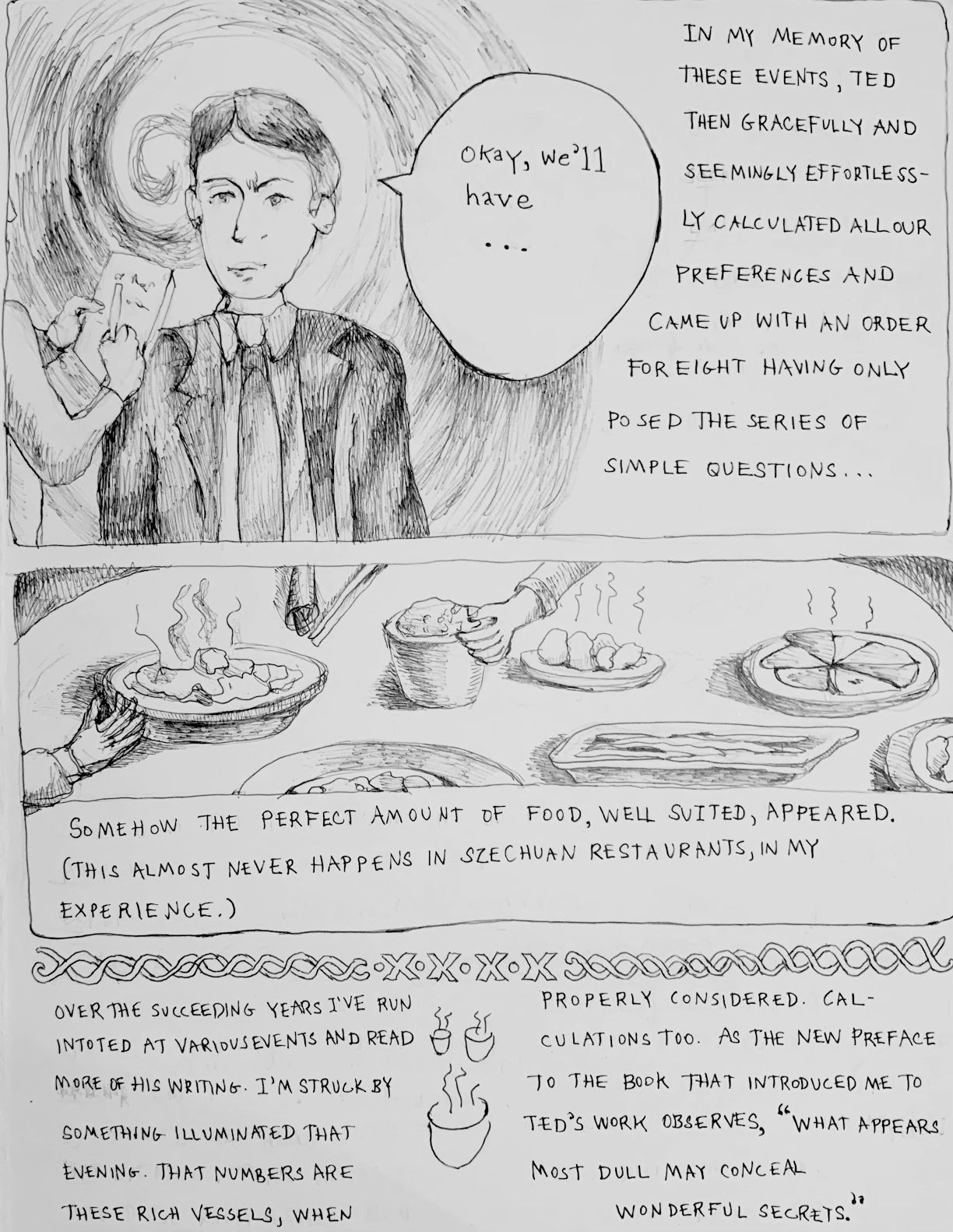

- Kevin Lambert GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER? TED PORTER

- Martha Lampland TED PORTER

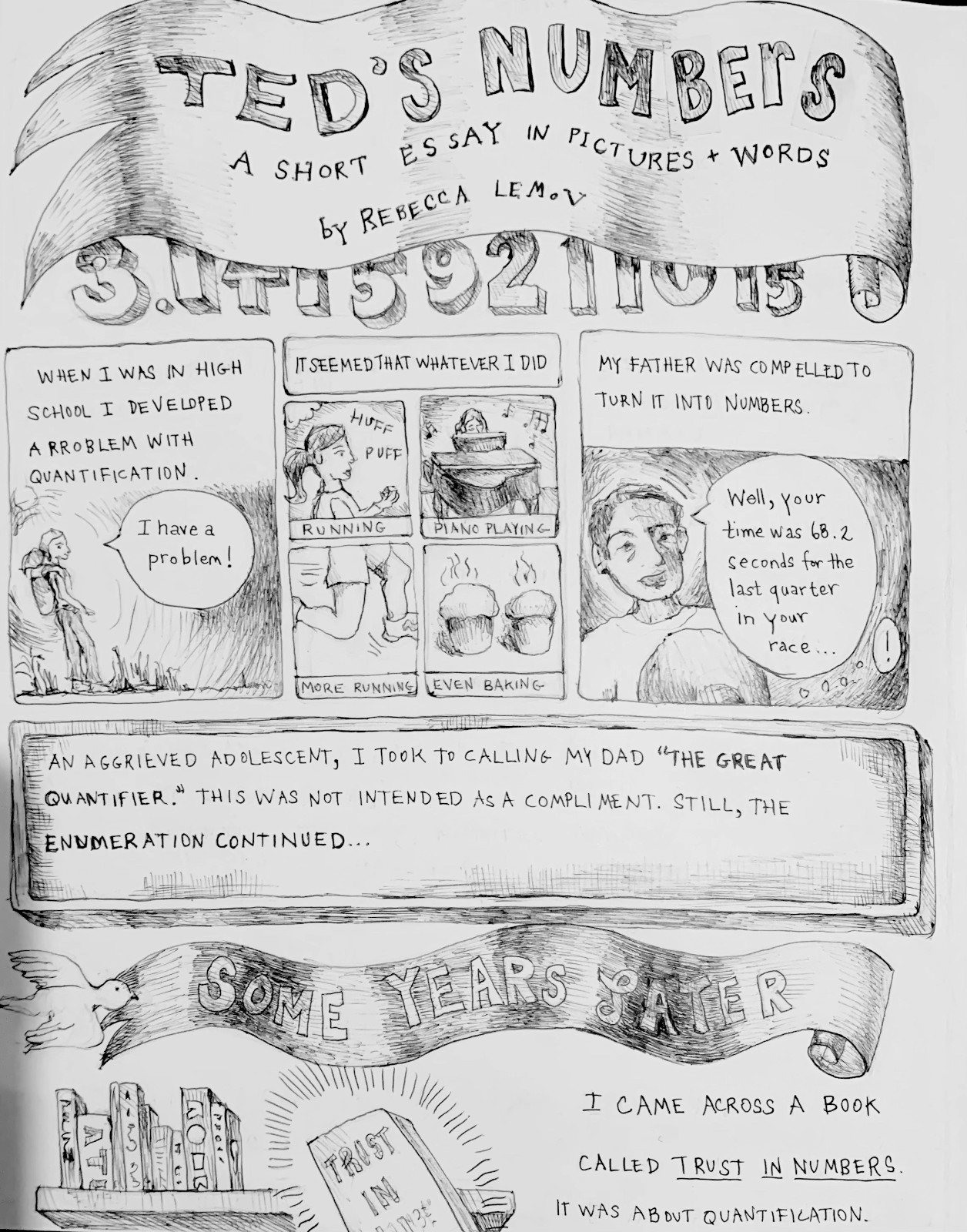

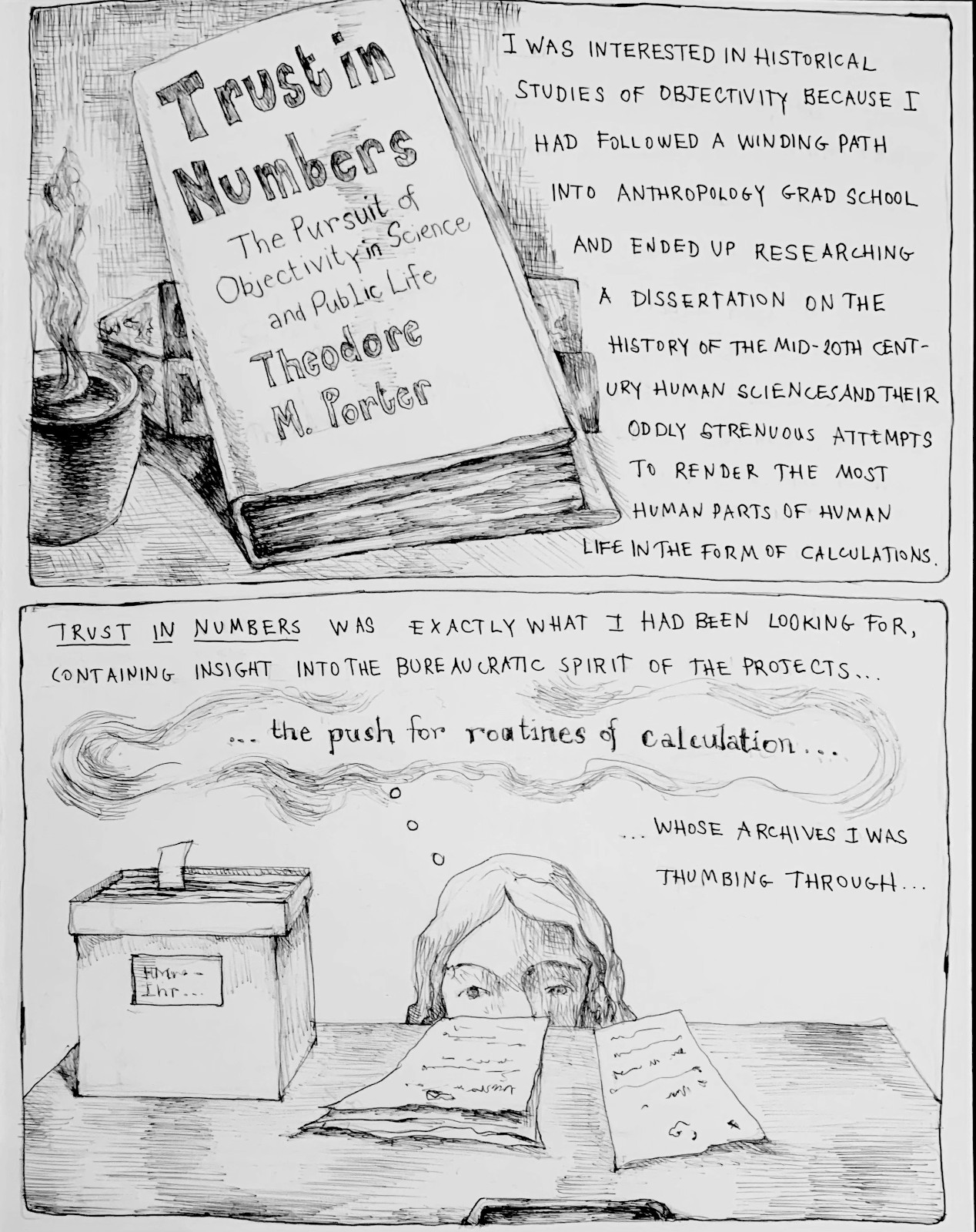

- Rebecca Lemov TED’S NUMBERS: A SHORT ESSAY IN PICTURES & WORDS

- Ilana Löwy NUMBERS AND CONSOLATION

- Harro Maas STROLLING AROUND AND FINDING THINGS OUT

- Andrea Mennicken TRUST, DISTRUST AND FUNNY NUMBERS IN ACCOUNTING

- Martine Mespoulet SOLVING A RIDDLE

- Peter Miller TED AMONG THE ACCOUNTANTS

- Mary S. Morgan TED’S OBSESSION WITH NUMBERS

- Christine von Oertzen PAULINE’S PETITION

- Jahnavi Phalkey ALL BECAUSE OF TED!

- Paul-André Rosental A DEMOCRATIC AND SOCIALIST TRUST IN NUMBERS: JEAN JAURÈS AND THE 1910 LAW ON WORKERS’ AND PEASANTS’ RETIREMENT SCHEMES

- Richard Rottenburg SINNVERZICHT, SINNVERLUST, SINNBILDUNG. A READING REPORT FOR TED PORTER

- Margaret Schabas TED PORTER, STALWART SCHOLAR AND FRIEND

- David Sepkoski TED PORTER: MAKING THE DULL EXCITING

- Ida Stamhuis MANY NUMBERS, TWO WHEELS

- Stephen Stigler MY CORRESPONDENCE WITH TED

- Jessica Wang TRUST IN TED

- M. Norton Wise FROM THE OFFICE NEXT DOOR

Preface

How many scholars over the course of their careers come to be known as founders of a new field of study? Theodore M. Porter is such a person. The field is Historical and Social Studies of Quantification. It crosses over from Ted’s own beginnings in history of science to people working in sociology, economics, accounting, biological evolution, and philosophy. Even more unusually, perhaps, Ted is not only admired but loved by all of those people who have found their own inspiration for work in the field they were creating with him, partly from simply reading his publications but especially from direct interaction with him. Even on the printed page, Ted’s wit and deep humanity impressed his readers, as well as his brilliance and learning. This volume collects some of their personal memories of those interactions. It is an appreciation of his personal qualities as a scholar and a friend. It marks the occasion of his retirement after many years at UCLA.

Although these brief reflections on Ted and his numbers do not aim at an academic exposition of his intellectual work, that work is nevertheless a constant reference point. A full CV would list six books, over a hundred articles, many, many reviews and comments, and a constant presence at workshops and conferences throughout Europe and North America. But everyone would agree that Ted’s position as founder of a field rests on four major books, each of which is wholly original and constitutes a pillar of Quantification Studies. Because our authors typically refer to these works only implicitly or in short form, we give them here with full citation.

The Rise of Statistical Thinking, 1820-1900 (Princeton U. Pr., 1986) appeared when no synthetic history of statistics yet existed (although Stephen Stigler’s important book appeared in the same year). But Ted’s volume was not simply a history of statistics as mathematics; it was a history of statistical thinking, and that made all the difference. He showed that statistical thinking throughout the nineteenth century and beyond was shaped by analogies drawn from social, political, and economic concerns. That theme has run through his work ever since.

Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life is Ted’s most famous book. In it he proposed the thoroughly counterintuitive thesis that the ubiquitous appeal to numbers to establish policy goals in modern democracies derives not from the professional strength of their state bureaucracies but precisely from their weakness. The numbers, established by fixed rules and methods for measurement, provide objectivity in the sense of non-subjectivity, non-dependence on the personal judgement of any individual.

Karl Pearson: The Scientific Life in a Statistical Age (Princeton Univ. Pr., 1995) draws on a massive archive to narrate the life of the founder of modern mathematical statistics. But the brilliant innovator emerges as a complex personality, one as deeply rooted in disparate social developments as was statistics itself. As Pearson himself put it, “It is impossible to understand a man’s work unless you understand . . . the state of affairs social and political of his own age.”

Genetics in the Madhouse: The Unknown History of Human Heredity (Princeton Univ. Pr., 2018) tells us in its title that we are going to be surprised, that the history of heredity is not the history of the gene. Genetics has been critically important in the twentieth century of course, but its story emerged from a much longer one on heredity as the supposed basis of mental illness and on the attempt to quantify its effects in statistical tables. This was the work of asylum directors and doctors, who in different countries and in different ways sought to rationalize their practices through quantification. Ted’s story is one of state institutions, social policies, and governance. He has taught us that this scenario has been typical in the history of statistical analysis.

We thank Ted Porter for his continually enlightening intellect and for his unfailing kindness and humor.

Simon J. Cook of Rounded Globe has kindly guided us through the process of making an ebook.

Aurélie Slonina has created our cover design. We thank her warmly.

Ken AlderINTRODUCING TED

In 2007, Ted asked me to introduce him for his ‘Distinguished Lecture’ at that year’s History of Science Society meeting in Arlington, Virginia. I take the liberty of reproducing that introduction here (lightly edited for clarity) because it expresses how I felt then—and still do.

This is an awkward introduction for me to make, but not for the reasons you might think. It’s obviously not because I’m going to say something critical about Ted’s work. The occasion alone makes it evident that I’m going to say something complimentary. But that is what makes this so awkward. I can’t joke around. I have to tell you honestly how I feel about his work. And to be honest, I have to say that I love it. The reason that this is awkward to say is not because academics are supposed to be critics all the time and pick apart everything we read. No, lots of us admire one another’s work, and there is no shame in admitting this publicly and often.

The problem is that I didn’t say that I “admired” Ted’s work. I said that I “loved” it. Which points to how oddly constrained we are in the sort of language we’re allowed to use in the polite society of academia. Sure, we are expected to pile up stacks of positive adjectives in our letters of recommendation, in our referee reports, and in our evaluations for tenure and promotion. But we remain oddly dispassionate about our superlatives. All of our adjectives are so—dare I say it?—‘objective.’ We use words like ‘excellent’ and ‘superb’ and even ‘superlative,’ as if we were evaluating academic work on a monotonic, single-factor sliding scale of superlativeness. Whereas if I were to speak truthfully and from the heart—and not as the sort of introducer who is expected to explain how Ted Porter’s work is analytically insightful and important to the development of the field—then I would say that I love his work because it mattered to me, subjectively.

I first read Ted’s work while I was trying to transform my own shambolic 800-page dissertation into a book, and his work helped me solve the central intellectual puzzle I had been wrestling with—even as it gave me scope to think for myself. I think we should honor this sort of intellectual gift more than any other; a style of thinking that gives others scope to think for themselves. I’ve always loved that in Ted Porter’s books and articles. Trust in Numbers came first for me, then The Rise of Statistical Thinking, and later, Karl Pearson; plus his contributions to the Bielefeld collective.

Almost all of Ted’s work is organized around a singular subject—the history of statistics—but each of his books follows a different set of frazzled experts as they wrangle over how to assemble their peculiar sector of the infrastructure of modernity. What these books taught me was that historians could reverse-engineer that messy process. Ted is famously the man who can make the history of statistics funny. And much of his ironic humor, I now think, comes from the disjuncture between that messy process and the final product. It’s an eye-opening lesson.

But now I’m drifting into appreciation, which is exactly what I promised I would avoid.

So let me say instead that what mattered to me—both then and now—was that Ted’s work showed me that there was a way to write the history of science that made me enjoy writing the history of science. Imagine that: the history of science as a joyous kind of work! And it was that, more than anything else, which made me love it.

And then, shortly before my own book came out, Ted and I met in person and we became friends, and this made me like academia too. (Note that I said “like” academia, not “love” academia, but then, I also promised I’d be truthful.)

Which is why I am delighted to introduce Ted Porter, who is going to explain ‘How Science Became Technical.’

Margo AndersonENCOUNTERING TED

My memory is hazy here, but I know I was reading and learning from Ted’s work some 40 years ago as I started venturing into the history of statistics and state-based data systems.

My initial interest was trying to figure out why historians and folks in general didn’t recognize how important the census was to American politics, to the cultural understanding of America, why folks treated it as ‘objective’—like an old shoe that was sort of just there, truth, easy to see.

I’d come at my interest in the census from a very practical place. I was using a lot of census data for a quantitative dissertation in urban and labor history, analyzing occupational change over time, and I kept being frustrated by the inconsistencies I found in the data I was retrieving. Why did the census reports in some years have these kinds of tables, and in other years, they didn’t. Why did some time series break and others didn’t? Like a good historian, I went to the old journals, and to the archives, the National Archives in particular, to look at the historical records of the census takers. What did they think they were doing? What did they mean by various terms, classifications, controversies, at the time the data were published.

I opened a much bigger Pandora’s box than I expected, managed to get enough insight to do the dissertation, publish it in a really obscure book series, and then turned my attention to the bigger questions that I now thought were embedded in the history of state-based quantitative data systems.

So a new venture into the history of science and technology to see who else was working on these questions. And I found Ted’s Rise of Statistical Thinking. Not his book alone, of course, but what Ted’s work did for me was introduce me to the European scholarly world and the history of science world on these matters. So, that book and all his later work have anchored me ever since, while I ventured in a somewhat different direction, namely into an ‘American case,’ the ‘politics of numbers,’ historical analysis of the policies surrounding official statistical data collection and use, and the really complicated intellectual world of statisticians, computer scientists, politicians, social scientists, humanists, and the public who determine these things.

I last was able to spend some time with Ted at the 2017, EU organized, Power from Statistics Conference in Brussels. We were staying in the same neighborhood near the conference, and were able to chat, share interests, generally catch up at the conference and at dinners that week. Genetics in the Madhouse wasn’t out yet, but I learned about the book, his European research, again, matters that I would not have encountered in my ‘American’ scholarly world.

It’s been a long scholarly conversation, threads picked up years, if not decades apart. And it should continue. Happy Retirement, Ted!

Fabrice BardetSTATISTICS AND ACCOUNTING(S), A MATTER OF COLLECTIVE TRUST, AND VICE VERSA

For the historians of tomorrow, a book could appear as the cornerstone of the new science that studies the growing role of the quantification of the world: the work of the historian Ted Porter, published in 1995, Trust in Numbers. The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life (TN).

While academic endeavors to promote a sociology of quantification are multiplying, in bringing together under the same prism quantifications of very different natures, sometimes physico-chemical, sometimes statistical, sometimes accounting or even financial, TN constituted a vanguard. In this first respect, the work had an important impact, in particular in France where Alain Desrosières, who was to quickly forge solid links with Porter, had just published the reference book of the French school of sociology of statistics: The Politics of Large Numbers.

Porter had participated in the famous Bielefeld seminar which led to the publication of The Probabilistic Revolution (1987), well known to those who are engaged in the development of the history and sociology of statistical science and statistical data. He himself had taken the material from it for his book The Rise of Statistical Thinking, 1820-1900. And in this dynamic, he had first considered looking into the mathematization of economics.

But passionate about science ‘in society’ and considering the economy too often cut off from the field of public action, he had finally decided to take an interest in the technologies mobilized by managers, these hybrids of science and politics that he refers to as ‘trust technologies.’

His idea is that quantification is as much the work of science as that of the political contexts in which public powers or companies impose themselves on the expert or managerial professions, science being ultimately often reluctant to quantify and more fond of the establishment of laws and theoretical models: “Quantification is a social technology (…) closely allied to the practical world of commerce and administration” (TN).

His research on statistical science and its various associated quantifications had offered him a first field of investigation on these technologies. His interest in economic history suggested a second: financial quantifications. TN thus offered an unprecedented cross-sectional look at these two forms of quantification built and mobilized to establish trust conducive to good governance.

Looking at statistics and accounting in a transversal way was Porter’s epistemological coup de force which marked the field of HSS research. He upset the lines, in France in particular where Desrosières, at the same time as he imposed on his students the reading of TN, reconsidered the direction of his research: he, the administrator of INSEE who had become a sociologist of statistics, extended to accounting his perspective and gradually saw it as a “historical sociology of quantification.” He first formulated it on the occasion of a symposium organized in 2002 with Eve Chiapello and in which Ted Porter was one of the two keynote speakers, alongside Peter Miller. He finally made it the title of a book (2008). This influence of TN on the French school is the reason for its judicious translation by Les Belles Lettres.

When the French edition of TN was published in 2017, the stakes in the academic field were doubly reversed. For all the heirs of The Probabilistic Revolution (and others), it had become obvious that statistics and accounting should be subject to the same sociological perspective. TN had won its first victory: unifying the sociological study of the numbers that build collective trust in science and public life.

But between 1995 and 2017, a second reversal occurred, within the very field of financial quantifications, directly linked to a notion that had emerged in the meantime: ‘financialization.’ While financial accounting has been established since its genesis (from the 14th century in Europe) ‘in historical costs,’ international standardization, driven in particular by the European Union (which adopted IFRS in 2002) has opted for new accounting ‘at fair value.’ This requires considering that behind the banner of numbers (financial accounting in particular), we have to design a sociology of their various families, associated with rival agents and interests. It is precisely the second track that TN proposed, in a less visible way (i.e. vice versa).

In TN, Porter reviewed various varieties of financial quantification: classical accounting, contemporary with the first capitalist economies, the cost/benefit calculations associated with public works or the probabilistic calculations of actuaries, both enjoying success in the nineteenth century, the first rather on French and American soil, the latter first on English. And for each type, Porter recalled the political contexts of their development as well as the pioneering works on which he based his enterprise: those of Lorraine Daston on the first mobilizations of probabilities in the conduct of societies, those of A. Loft or T. Johnson and R. Kaplan on the rise of managerial accounting in the twentieth century, by T. Alborn, R. Parker or Mike Power on the probabilistic shift in financial accounting, or even by F. Etner and A. Picon concerning the economic calculation of French engineers, and M. Keller about the US Army Corps of Engineers.

And through this fresco, Porter sketched the see-saw of financialization that no one yet called that. Exhuming a 1963 article from the Accounting Review which engaged the criticism of the positivism dominating the accounting profession clinging to the myth of ‘absolute objectivity,’ then another from a 1977 which took up the controversy to promote the new financialized techniques of accounting (based on ‘fair value’) whose use was beginning to spread among practitioners, Ted Porter shared with his friends from the LSE, Peter Miller (1991) and Mike Power (1992, 1993, 1994), the intuition that financial accounting was going to experience a revolution. He suggested to consider that behind the banner of quantifications hide rival families. Now that the financial revolution has taken place, TN can fly towards its second victory: to distinguish the new numbers of trust, those of contemporary financialized accounting which now dominate those of historical financial accounting, and thus illuminate the new distinction.

Jean-Pierre Beaud & Jean-Guy PrévostTRUST IN PORTER

Where to begin? Our very first encounter with Ted Porter goes back to the 1992 Social Science History Association meeting held in Chicago, at a time his first book and the output generated by his participation in the 1982-83 Bielefeld seminar had established him as a rising scholar in a rising field to the establishment of which he was playing a major part. But closer links developed when Ted generously accepted our invitation to act as keynote speaker in a 1999 conference held in Montréal on L’ère du chiffre/The Age of Numbers. As the bilingual title and the French spelling of the city indicate, language is here a political as well as an existential issue. Therefore, we both greatly appreciated Ted’s concern in this regard, his willingness to speak French more and more often and more and more fluently as he came back to Montréal (he of course could read French perfectly way before that, as can be seen from the primary sources he used in his 1986 The Rise of Statistical Thinking). And come back he did, regularly, as scientific advisor to the Centre interuniversitaire de recherche sur la science et la technologie from 2008 on, to take part in events such as the 2011 meeting held on the occasion of our institution’s bestowing of an honorary doctorate to Alain Desrosières and the 2017 conference Le chiffre et la carte, where he delivered the inaugural address, or in summer schools held in various universities.

Ted’s Francophilia meant of course that he has also been very present in France since the start of his career. Trust in Numbers—with a chapter devoted to the École Polytechnique and French engineers—was already frequently quoted and a source of inspiration for many French scholars when it was translated and published in 2017 as La confiance dans les chiffres. Beyond France, one’s path could also cross that of Ted in Italy—where Le Origini del Moderno Pensiero Statistico had appeared in 1993—or Spain, two countries where scholars devoted to the history of statistics have found in his work ideas, concepts, and insights to guide their work. The same can be said of Latin American scholars, as evidenced in the recent edited book Socio-Political Histories of Latin American Statistics. And while neither of us is familiar with the Japanese academy, we observe with amusement that both The Rise and Trust have been translated in Japanese, something that neither the French nor the Italians have done. If Adolphe Quetelet, a central figure of Ted’s first book, has been described as “the travelling salesman of statistics,” then maybe the same can be said of Ted regarding the history and sociology of statistics.

To be sure, Ted, besides being a towering figure in any group given his height, is a dominant intellectual presence in this field. A few words about his scientific contribution are thus in order, even though this is not the place to conduct any elaborate explanation or discussion. We would like to briefly underline one aspect of his work. To tentatively translate Alain Desrosières’s phrase aller au charbon, we may say that, as the coalminer who goes down the pit, Ted likes to dig deep into the archives. His most recent book offers a good example of this: we remember how startled we were the first time we heard Ted presenting on this subject, as he quoted passages from reports written by forgotten asylum directors and displayed old maps and tables about the varieties of “madness.” We wondered: Where will this lead to? Are we going to emerge from the mine? Well, we did, and the result was Genetics in the Madhouse, a book whose breadth, empirical wealth, and relevance to contemporary concerns have been hailed. There is in our view a moral quality attached to this intellectual posture, and it is humility, which is indeed, besides generosity and simplicity, an endearing trait of Ted’s personality.

Merci Ted d’avoir jeté des ponts entre les États-Unis et le reste du monde, entre l’histoire et les sciences sociales. Voyageur infatigable, conférencier toujours disponible, compagnon agréable. Le monde francophone te salue.

Luc BerlivetKNOWLEDGEABLE BUREAUCRACIES

I will forever be grateful to the late, and fondly remembered, Alain Desrosières for introducing me to Ted Porter’s work, and then to Ted himself, sometime in the late 1990s. Alain had first directed me towards Ted’s first, seminal book on The Rise of Statistical Thinking. But soon Trust in Numbers came out, and started attracting attention from the then-thriving French history of statistics scene – a mix of historians, sociologists, and STS scholars of all stripes. The pages on the Ponts-et-Chaussées engineers clearly struck a chord, especially among the many of them who had studied or worked at an elite French engineering institution. However, the comparative approach favoured by Ted, with its wide thematic and geographical range proved puzzling to some. This was not your “traditional monograph”; it was much more interesting than that. Moving away from a conception of statistics as the powerful linchpin of an expanding, control-seeking state, the book redirected our attention to the social basis of statistical authority: the complex negotiations and arrangements on which “quantitative expertise” rested. As a Ph.D. student working on the endlessly contested attempts by the French administration to weigh up the “social cost” of alcoholism and smoking, I found it especially illuminating. The widely commented chapter on the uses of cost-benefit analysis by U.S. Army engineers firmly established that far from being the prerogative of dominant state organizations the resort to quantification sometimes amounted to a weak-to-strong strategy. Another quality of Ted’s work, in my view, was his ability to weave together the history of statistics and the coming age of objectivity. This might sound surprising, considering the manifold links between these two research fields, but he was — together with Lorraine Daston — among the few who really thought through the entanglements between quantification and mechanical, as well as disciplinary, objectivity.

I kept learning a lot from Ted in the years since then. I believe the most crucial lesson he taught us was to distrust the traditional view of scientific innovation as a process by which scientific knowledge produced at universities, scientific institutions, and (increasingly) private firms gets “applied” to public problems. From his first book onwards, Ted strove to dispel this fallacious representation of knowledge production as a one-way journey. He certainly is among those who highlighted the role of bureaucracies as sites of scientific innovation, not just “applied science” (a reductive expression often used to describe statistics) but full-fledged scientific knowledge. Not only the most prestigious “bureaux”, staffed by distinguished mandarins, but also obscure and often neglected institutions, such as the “lunatic asylums”, “schools for the feebleminded”, and prisons occupy centre-stage in his last opus so far, provocatively but aptly titled: Genetics in the Madhouse. This is an important book in many ways. Not only does it establish that shady, underfunded organizations, in the United-States, Britain, Germany, France, and other European countries, were important sites of knowledge production, even on topics such as medicine and human heredity that far exceeded the realm of the social sciences. But the book also widens the perspective of an entire research field, the history of human heredity, by highlighting the scientific relevance of lunatic asylums and related institutions, whose importance had been seen as merely political (the rising tide of mental diseases was fuelling the great fear of “degeneration”). In so doing, Ted also invited us to revisit the relationships between heredity and genetics, while shedding new light on the links between psychiatry and eugenics.

For all their differences in topic, Trust in numbers and Genetics in the Madhouse share important similarities – catchy titles being only one of them. They are wide ranging books, both from a chronological and a geographical perspective; their approach is comparative in nature; and they are both built on a thematic framework. Ted’s other major book, which interestingly came out in-between the two aforementioned, is of a strikingly different kind. Karl Pearson: The Scientific Life in a Statistical Age is neither a traditional biography, nor – strictly speaking – the history of a life-in-context, but rather a reflection on “an improbable personage”1. The book, which is of great importance to anyone with even a passing interest in the history of statistics, also has a nice reflexive twist. Ted ironically plays with the genre of biography to explore the coming of age as a scientist of the young, romantic Karl Pearson, entranced with Bildungsromane. As improbable as it might seem, the personage who – perhaps more than anyone else – has come to epitomize the rationalisation of the modern world was so enthralled with Goethe that, at the age of twenty-three, he wrote a partly-autobiographical novel transparently titled: The New Werther…

I am certainly not the most competent person to comment on Ted’s style of writing. Still, there are important features of his work which I quickly came to recognise, and appreciate very much. Meticulously researched, scholarly impeccable, sophisticated in exposition, his texts testify to a high level of intellectual engagement with the topic, not to mention a certain sense of humour – dry humour, that is. Every seasoned reader of Ted’s prose will have their own favourite quote, here is mine: “Although Trust in Numbers seems to work as a memorable title, it can mislead.”2 These are the same qualities I have seen in the man-beyond-the-author as I have become friends with him. He is a friend I am looking forward to meet again soon.

Dan BoukCOUNT ME

Count me among Ted’s numbers, maybe even as a ‘funny’ one.

As Ted’s work has shown, repeatedly, there is nothing simple about translating the world into numbers. “Thin description” is a thick process.

So, how did I end up as one of Ted’s numbers?

It all began with a footnote.

In 2002, I was finishing up an undergraduate degree in computational mathematics. Over the course of four years of calculus, linear algebra, and (alas) analysis, I’d determined that I enjoyed (most) mathematics, but that I longed to be closer to the beating heart of humanity. The math I encountered in the classroom seemed committed to ignoring our shared social world.

At the same time, I was reading Louis Menand’s The Metaphysical Club and trying to figure out what to do with my life. Menand devoted a chapter to the Peirce family’s use of statistical methods to expose potential foul play in an inheritance case. It was a good and rousing story, but the footnotes proved far more consequential. When I look back at them today, I see that they included a whole host of worthy books. But at the time, one title caught my eye in particular: The Rise of Statistical Thinking.

A universe of possibilities yawned before me. My heart raced.

In 2004, I decided to apply to graduate school in the history of science. But first, I bought a plane ticket to Cambridge, MA and signed myself up to attend the annual meeting of the history of science society. I attended every session I could, hungry to make sense of this new field. Today, I only remember one talk.

There, before me, (standing much taller than I had expected) was Ted Porter, who proceeded to read aloud (in his resonant baritone) a text derived from a book he had just completed. It was a moving performance, like a virtuosic aria performed by the composer. Ted set his piece—his story—in a tragic mode. His subject, Karl Pearson, distrusted specialization and he found its antidote in science. Yet, and here was the tragedy, the work he did instead ushered in an age of narrowing expertise and mechanized decision making.

Ted felt no need to reconcile or apologize for the tensions and contradictions of his subject. Ted offered up Pearson the racist and eugenicist alongside Pearson the feminist and socialist, an author of medieval passion plays and the evangelist for statistical method. Pearson worried his own full self would one day be reduced to a name on an integral, which in a way it was. I did not really feel bad for Pearson, and Ted did not ask that of me: I felt instead the weight of a lost dream of thinking selves left whole and free, a dream that Pearson upheld and also undermined. Ted’s paper appealed to my moral imagination, as well as my intellect. It proved that the history of science could be written as literature.

In the years to come, my formal education led back—again and again—to Ted. His work made the work that I was drawn to possible. I am a historian of quantification and I teach a course titled ‘The History of Numbers in America,’ and so it won’t surprise anyone that I say Ted laid the foundations for what I do. He arrived on the scene as part of that miraculous authorial cohort in the mid-80s who nearly simultaneously published landmark books: Raine Daston, Ian Hacking, Steven Stigler, Ted, and the rest of the Bielefeld gang. Whenever, in years to come, I felt the tug of territorial feeling, whenever I worried that, for instance, too many other people were researching risk, I took solace in the story of that group. There could be strength, and not competition, in scholarly numbers.

But when I say Ted made my work possible, I am not only thinking about his leading role in the study of quantification. Just as important, and possibly more so, was the way he championed the study of science in unconventional settings. In another field I cared about—the history of the life sciences, Lynn Nyhart or Rob Kohler had made the case for finding lost stories in field and experiment stations. Such work made it legitimate for someone like me to go looking for science outside of laboratories, and even outside universities. Ted’s Trust in Numbers has meant many things to many people. For me, it meant first and foremost that a historian could credibly go looking for science in an asylum or the Army Corps of Engineers, or most importantly for my purposes, in a life insurance company or a census office.

I count myself enormously fortunate that Ted counted me as one of his number too. There was no reason for him to ask to read my dissertation in 2009 and even less reason for him to actually do so, sending me within the same month half a dozen meaty paragraphs of comments, questions, and encouragements. “Some kind words from a huge figure” I exclaimed at the time in an email to my partner and parents. It was only the beginning: as Ted proved unfailingly generous—writing me letters of support, stepping in to save my first book after a lacerating anonymous review, and then inviting me to UCLA to give my first talk after that book came out.

I know that Ted intended for his work to help expand our search for science and its histories, because he told me so—at HSS panels and in private. His actions amplified those words. I look at my own cohort of scholars and those who have followed and I think it is clear that he succeeded. Count me among Ted’s numbers, I say, alongside so many others.

Bruce G. CarruthersON THE INEFFABLE TED-NESS OF TED

The first time I met Ted Porter was in print, when I read his wonderful 1995 book Trust in Numbers. It was undoubtedly at the suggestion of Wendy Espeland that I read it, but I would like to think that I discovered Ted all by myself. It could also be that learning regression analysis from Stephen Stigler cultivated a perverse and mostly latent interest in the history of statistics. Whatever the cause, I wasn’t surprised that Trust in Numbers received such great acclaim, because for me it possessed an alluring set of qualities. First and foremost, it provided a richly documented historical analysis offering some profound ideas about quantification and its applications. In 1991, Wendy and I had published an article on the history of double-entry bookkeeping, so Ted’s discussion of cost-benefit analysis was like the call of the sirens. In addition, however, a distinct authorial personality shone throughout the book: a personality given to very dry, understated wit and self-deprecating erudition. Normally quantification isn’t a laughing matter, but some of Ted’s lines were so clever I just burst out guffawing mid-paragraph. This loud merriment has earned me a few stern glares in the library, and perhaps a ‘shush’ or two.

Then I heard Ted speak in person at Northwestern University, giving a public ‘Ted talk’ at the invitation of my colleague from the history department, Ken Alder. Ted’s authorial personality was there in the flesh, and I was delighted to realize that the man speaking behind the lectern was the same as the man I had met before in print: witty, self-deprecating, learned, and ready to make an important argument. Even more impressively, his erudition wasn’t something stored on his office bookshelves or contained in files and notes: it actually reposed in his brain, ready to be retrieved on the spot!

Spending a year together at the Wissenschaftskollegg in Berlin sealed the deal. Along with other members of the ‘quantification group,’ we were able to think hard about a number of issues, working on separate projects but doing so together. It was a great year, offering the perfect balance of intellectual stimulation and sheer fun. Ted impressed me with his commitment to bicycles and opera. And through Ted I met Mary, another gift of that year. My project eventually turned into a book about the history of credit, published in 2022. Ted’s project became Genetics in the Madhouse, published in 2018. Thank goodness scholarship isn’t a race, because Ted would beat me every time.

Academia is now changing. Increasingly, people maintain a social media presence, and supplant peer-reviewed publications with fights on Twitter, academic selfies, and blog-posts that have a short shelf-life. Ted would not thrive on Twitter, or any such platform encouraging hair-trigger showboating or performative bloviation. He is simply too thoughtful. He isn’t arrogant enough. He knows too much to feel comfortable making caricature summaries or bald assertions. In short, Ted possesses the marvelous and invaluable quality of ‘Ted-ness,’ which is made manifest in all he has done. Where did Ted acquire his Ted-ness? There is some dispute about the matter, and reasonable people can disagree, but it seems to be the result of having grown up in the Pacific Northwest, a breeding ground for rare academics. He is now retiring after a very accomplished career, but he will always remain himself. And what a wonderful self he is! I will be forever grateful that I have had the chance to witness Ted-ness up close and in person, practiced by the man who practically invented it. Thanks to you, Ted!

John CarsonSOME WORDS AND PICTURES APPRECIATING TED AND HIS NUMBERS

When I first encountered Ted Porter he was a shadow; well, a shadow presence anyway. He was in his fourth—and final!—year of graduate school but was already long gone, finishing up elsewhere his brilliant dissertation, ‘The Calculus of Liberalism,’ that would become his first book. I don’t remember if I met Ted that year, but I knew of him, the grad student who would finish in near record time and who managed to earn the admiration and respect of each of the Program’s faculty members (no mean feat). Ted was soon off to CalTech on a postdoc and then a job at UVA before his final landing spot at UCLA. Our paths I know intersected at HSS meetings, both because of our overlapping interests in quantification, measurement, and the human sciences, and because of the notorious Friday night ‘smokers’ where everyone ever connected to the History of Science program and their friends eventually ended up.

Ted, of course, was not a figure one could miss: tall, smart, and with a gravely deep voice, he stood out, even before he spoke, and even more so after, when you realized that he had just asked a profound question or provided some acute insight, often with a little dash of deadpan humor for those attentive enough to catch it. It took me a while to learn that; once I did I delighted even more in the chances to hear Ted speak, knowing that if you listened carefully, you were assured of being amused as well as edified. I don’t have any clear recollections of our early encounters, but I do still remember vividly a talk Ted gave at Princeton. It may have been in Spring, 1992 and I think it was for ‘The Values of Precision’ workshop where I was the commentator. The subject was the role of quantification and numbers in early Victorian life insurance, a seeming snoozer if ever there was one.

The overall theme of Ted’s talk, if my yellowing notes are at all accurate, presaged one of his key arguments in Trust in Numbers, that mid-19th century British actuaries characterized their expertise as deriving not from their mastery of precise quantitative techniques, but rather from their character, as gentlemen of skill and judgment. They did not reject quantification so much as deny it pride of place, arguing that computation and judgment must be combined. The push for mechanical forms of objectivity arose outside of the actuarial sciences, Ted argued, from the demands of lawyers and members of Parliament, what Ted would later characterize broadly as political and administrative culture. What has kept that talk in my memory for so many years, however, was the way he opened it, by pointing out that the practice of life insurance, particularly in the nineteenth century, was based on a paradox. In simple terms, life insurance companies only wanted to sell their policies to people who didn’t want to buy them. If someone wanted life insurance, Ted pointed out, the reasonable suspicion was that they knew something about their health, or were about to engage in some endeavor, that made them a bad risk. Lacking independent ways of determining who was or was not likely to die, prudence dictated being skeptical of those who thought they might expire soon enough to need insurance. The point is still funny, at least to me, and also, I think, profound. How do you entice people who don’t want a product to buy it, and how do you come up with a price that will attract the right sort of person and will also maintain the financial solvency of the company? Ted used this observation as a jumping-off point to do what he has done so well in so much of his work: explore the tangle of science and culture, of quantitative and qualitative, of mechanical and experiential, of hard sciences and so-called soft sciences.

When I think about Ted’s numbers (which I probably do too often, or maybe not often enough), I never think about them alone. In his telling, they always result from people (or instruments) doing work, and are always part of complicated discussions and negotiations among multiple actors. Ted’s numbers are social beings, turned to as often in moments of weakness as of strength. They don’t reveal the underlying nature of the world, whether natural or social, so much as help make it. In some ways they are kind of like Ted himself: powerfully able to help remake the intellectual landscape, and quietly social beings.

I was asked a number of years ago to write a recommendation for Ted for a MacArthur Fellowship (so much for keeping it a secret). I still don’t understand why he wasn’t awarded one. I argued then and would argue now that his work on the history of quantification and statistics more than deserves it. I observed in that recommendation that “Professor Porter stands out in the fields of history of science, science studies, and intellectual history for the range and originality of his scholarship. His work is smart, accessible, and profound in the ways that it reveals the texture of the interweaving of science with other cultural forms. He is not only read in fields well outside of history or science studies (including political science, sociology, literature, and philosophy), but publishes in venues unusual for an historian as well.” Ted’s most recent book, Genetics in the Madhouse, confirms these characterizations of his work, though also reminds me that I forgot to mention at least one critical additional factor: Ted’s work routinely forces us to reconsider what we thought we understood.

What comes next? Personally I’m hoping Ted will do an audio book on numbers and opera. But whatever he turns his attention to, I know it will be full of sharp insights, wicked wit, and probably plenty of funny numbers. Ted always has at least one eye looking out toward the future.

Karine ChemlaTRUST IN Π

For Ted

In line with Ted’s classic Trust in Numbers, I analyze here the central part played by the number 1620 in the management of grain in early imperial China. Previous scholars have emphasized the cosmological dimensions of the number and the artefact to which it was attached. I argue that 1620, whose decomposition into prime numbers is 22 ·34 ·5, reflects a complex administrative organization allowing different social groups with different mathematical skills to work together to manage grain. Moreover, I suggest interpreting the efforts experts in mathematics made to obtain better approximations of π as related to the project of getting 1620 with π. In my view, these efforts aimed at emphasizing how numbers were crucial to a form of social fairness.

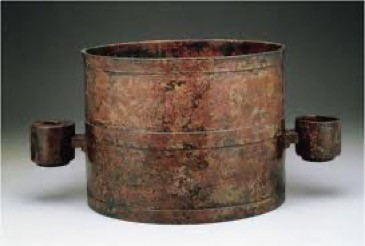

Wang Mang’s bronze hu

Wang Mang’s bronze hu

The argument relies on the first-century mathematical canon The Nine Chapters. This fact implies that mathematical works of this kind were intimately associated with the imperial bureaucracy. Many clues support this assumption.

In 656, Li Chunfeng finalized his annotated edition of this canon, to which he attached the commentary Liu Hui completed in 263. Interestingly, Li Chunfeng had previously authored historical accounts of measuring units and standards for dynastic histories. My argument combines both types of sources.

In general, the exegeses on The Nine Chapters focus on proofs of correctness of its algorithms. However, on three occasions we see the exegetes discussing the bronze vessel that Liu Xin designed in the early first century for Emperor Wang Mang, and also an inscription that this vessel bore. The vessel was the standard for the capacity unit hu. The inscription stated the numerical value of the diameter of the corresponding inner cylindrical cavity, with a high precision, and the related area and volume, respectively, 162 cun and, precisely, 1620 cun.

Liu Hui’s commentary mentioning the vessel follows three similar problems: cones of grain are formed on the ground (respectively, cones of unhusked millet, soybeans and husked millet mi). Given the circumference of the base and the height, the problems require determining the volume of the heap and the number of hu it contains. The computation of the volume clearly uses an approximation of π: this is the first clue of a link between π and the measurement of grain. The conversion of units of volume into hu attests to a striking phenomenon. In these problems, depending on the grain, the volume stated by The Nine Chapters as corresponding to one hu varies. For unhusked millet, soybeans and husked millet mi, one hu corresponds to, respectively, 2700 cun, 2430 cun and … 1620 cun. Weaving together the commentary and Li Chunfeng’s history of measuring units, we get several conclusions.

These hu could not express capacity. In fact, these units hu measured the ‘value’ of grain, 2700 cun of unhusked millet and 1620 hu of husked grain both corresponding to one value unit hu. Moreover, different hu corresponded to different vessels, each attached to a grain. In fact, in early imperial China, grains were a key product for the economy of the state: taxes were levied, and officials’ wages paid in grain. Determining equivalent quantities for different grains and different states of grain was crucial, and administrative regulations (which are quoted in mathematical writings) asserted numerical values to this effect, expressing them with quantities of volumes or capacity or else with vessels.

Consequently, to evaluate a quantity of grain, one could use the related vessel. One could also use any of the vessels measuring value and simple rules of three. Indeed, every number expressing the volume of one hu could be decomposed into prime numbers exactly like 1620 cun. Hence, converting one unit hu into another put into play numbers made of small factors. Finally, one could shape grain as a cone, using algorithms to compute the volume and then dividing by the volume corresponding to one value unit hu. The latter yielded better accuracy, but required greater mathematical skills.

The administrative organization of the system of grains thus allowed practitioners having different mathematical competences to work together to manage grain. In fact, the pivot of this system was the husked state of grain called mi, which was defined for both millet and rice and thus established a bridge between different grains. Interestingly, its value unit hu was the only one corresponding to the capacity unit embodied by the bronze hu. We see how the system of measurement units was rooted in issues related to grain.

Measuring a cone-shaped heap and using mathematics to evaluate grain yielded accurate results, if the approximation for π was accurate. Having a vessel whose inner volume was exactly 1620 cun was another basis for a fair measurement of the value of grain. One may interpret the inscription carved on Wang Mang’s hu as displaying the effort deployed to ensure fairness. The computation of the best possible value for the diameter of the bronze hu to get a volume of 1620 cun also involved an approximation for π: this is a second link between grain and π. In the fifth century, Zu Chongzhi worked on π in relation to this issue. The second commentary on The Nine Chapters dealing with the bronze hu bears precisely on the area of the circle and can be attributed to him. Zu used various values for π to assess how Liu Xin computed the relationship between the inner diameter of the vessel and the volume of 1620 cun. Considering this computation as inaccurate, Zu offered another value with high precision for the diameter of a vessel measuring 1620 cun.

Arguably, these values gave means to make correct standards. However, the third piece of commentary mentioning the bronze hu, which follows a problem dealing with a cylindrical granary, suggests an additional answer. If grain was essential for the state’s economy, granaries can be compared to banks. The granary in question measures a huge and integral number of hu of husked grain. Could the inscription on the bronze hu also serve to build cylindrical granaries and control the value of the grain contained? This is an open question, which might indicate yet another relationship between π and the evaluation of grain.

Roser Cussó THE MYSTERY LIVES ON

I had the honor, in 2012, of having Ted on the jury for my Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches (thesis defense) in Paris, together with other distinguished colleagues including Alain Desrosières, the founder of quantification studies in France.1 The Habilitation opens the way to supervision of doctoral students and research projects, and to professorship. The thesis title translates as ‘Compare and Conquer: History and Sociology of International Quantification,’ from Comparer pour mieux régner, and playing on ‘Divide and Conquer.’

The honor of Ted’s participation was twofold. First, being a pioneer of the history of statistics, he provides an inspiring and established framework for contributions like mine. The publication of The Rise of Statistical Thinking 1820-1900 in connection with the work of the Bielefeld group, defines a ‘before and after’ in the field. To wit, and as added evidence of the epistemological transcendence of the book, in the preface Ted acknowledges a giant in the field of the history of science, Thomas Kuhn, for his generous advice. Second, but no less critical, continuing the study of Ted’s work and following up on our exchanges from the Habilitation events, I looked more deeply into a fascinating question; the nature of the link between the statistics of International Organizations (IO) and their power, in comparison to the link between statistics and state power, innovatively analyzed by Porter.

The interaction of two fundamental insights opened rich possibilities for reflection; first, quoting from Ted Porter (Rise, p.17):

The modern periodic census was introduced in the most advanced states of Europe and America around the beginning of the nineteenth century […]. Most often, the chief purpose of this statistical activity has been the promotion of bureaucratic efficiency. […] Until about 1800, the growing movement to investigate these numbers in the spirit of the new natural philosophy was likewise justified as a strategy for consolidating and rationalizing state power” (italics added here).

And the other, quoting Adolphe Quetelet, at the first International Statistical Congress (1853):

Statistics, conceived in a spirit of unity and resting on fixed bases appropriate to all countries, are intended […] to extend its benefits to all countries and to shed new light on the true interests of governments” (translation and emphasis is ours).2

After my initial history and demography degrees in Catalonia, I found in Paris an academic ‘center’ for the development of human and social sciences as well as demographic and statistical theory and practice—and I think that Ted will agree that Paris also has some interesting cafés and cultural sites! Before my PhD, by a stroke of luck, an internship at UNESCO led to several years work there, notably in the Statistical Services, which lasted through my thesis preparation. My ‘peripheral’ origins and ‘outsider’ view of the great powers, as the main actors of the history of statistics, plus my experience as a practitioner, were all helpful to my ‘reconsideration’ of the idea of Quetelet via Porter.

Quetelet’s “fixed [statistical] bases appropriate to all countries” illustrates the international arena’s role in coordinating state development; with the Congress aiming to have censuses taken on a stable and uniform basis, among other recommendations. Statistics, seen as universal, was therefore global. Created later, IOs would come to treat states as the ‘individuals’ in their global series and calculations…

However, the statistical services of the IOs, compared to those of the states, cannot simply be seen as analogous under change of scale, nor merely reproducing and expanding a science that states had already developed. IOs also ‘construct’ states through ‘fixed’ international statistical conventions and ways of working and ‘thinking.’ After World War I, while the League of Nations guided ‘newly created’ and/or ‘peripheral’ states through statistical cooperation, the great powers also progressively complied with data frameworks. They all had to adopt harmonized policies such as free trade and the abolition of forced labor. “Consolidating and rationalizing […] power,” international statistics would finally shed “new light on the true interests of governments”. “True” or, at least, ostensible interests, one might add.

I would like to end this tribute to Ted and his influence, underlining a less examined, more personal aspect of statistics. We all have a special ‘relationship’ with data and its exploration. As a practitioner, I have been captivated, by the beauty of a well-executed statistical analysis, by the unexpected insights that can emerge—just as words artfully composed can illustrate ideas that have not yet found expression. Indeed, one may be struck by how our ability to translate the world into data, and analyze it, is an expression of human genius. Evidently, data is too often used to support preordained conclusions, yet, it takes alternative data and analysis to nurture and maintain, in turn, free and pluralistic debate.

The enigmatic, non-reducible character of statistics underlies Porter’s work, as exemplified in the beautiful expression Statistical Thinking. Alongside Ted, research into statistics lends itself to an understanding of the role of human intelligence in the history of science and moreover in that of culture. The rise of big data is writing a stimulating but disquieting new chapter, with the growth of both knowledge and surveillance capacities. The ‘statistical’ aspect is ever-present, even with recent evolutions, including the Bayesian revival, adversarial learning, etc., while predictions that ‘thinking’ is about to be superseded by ‘artificial’ intelligence are confounded by ‘natural,’ methodological skepticism. The story of statistics continues. As it experiments with new levels of self-reflection, the mystery lives on.

Notes

1. The other members of the jury were Alain Chenu who was my sponsor at the IEP in Paris, Corinne Gobin who had supervised my postdoc at the Free University of Brussels, Hervé Le Bras, director of my PhD at the EHESS, Olivier Martin, from the University of Paris Descartes, and Martine Mespoulet, from the University of Nantes.

2. Minutes of the First International Statistical Congress, 1853, p. 19.

Lorraine DastonTHE VOICE OF TED

The first time I heard Ted’s voice was in mind’s ear, but I immediately registered its distinctive timbre, pitch, and tone. I had been asked to serve as an external reader of Ted’s Princeton dissertation on the history of nineteenth-century statistics, a sign of how sparsely that field was populated back in the early 1980s. I had finished my own dissertation on probability and statistics in the Enlightenment only a few years before and was hardly an authority in the field. The dissertation, which would become The Rise of Statistical Thinking (1986), richly repaid the reading. Quite aside from the impressive research across numerous disciplines and intellectual traditions and the originality of the analyses, the dissertation was written with élan and esprit. I often found myself rereading certain sentences, simply for the pleasure of the cadences and the delicate irony. There was something distinctly Victorian about the diction—the symmetry of the syntax, the self-assurance of the judgments, but also the sharp eye for the droll and the odd: imagine a history of statistics written by Trollope. It was unique among all the dissertations I have read before and since in lending itself to being read aloud.

So I was delighted to learn that Ted would be joining the research group Lorenz Krüger, Ian Hacking, and Nancy Cartwright had organized on ‘The Probabilistic Revolution’ at the Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Forschung in Bielefeld during the academic year 1982-83. The project kicked off with a conference at which we all presented our projects, and I can still recall how Ted’s voice—this time in person—reverberated in the ZiF lecture room. It was a voice made for the lectern, the pulpit, or the stage: deep and resonant enough to reach the last row without a microphone. Many years afterwards in 2014, when Ted spent a year at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, Ted and I gave a brief reading of science-related texts (as I recall, excerpts from Mark Twain, William James, Thomas Carlyle, and Mary Shelley) at the English Theater of Berlin, and when I ran into the theater’s director a few years later, he was still enthusing about Ted’s excellent stage projection.

At the weekly meetings of the ZiF research group, I learned to listen for a slight change of inflection in Ted’s voice, from the matter-of-fact to the mock declamatory, which signaled a delicious (and deliciously dry) jab at some absurdity or pomposity. The targets could be some long-dead Victorian sage, such as Henry Thomas Buckle, or someone in the room—if the latter, those of us who savored Ted’s subtle humor tried not to giggle in appreciation. When we were not discussing various episodes in the history of probability and statistics, trying to write our books, and discovering the delights of German breads and cakes, those of us who were not native speakers of German were trying to improve our skills in that language. Ted and I had different strategies: I labored, largely in vain, to perfect my accent; Ted was in contrast a demon for grammar. I can recall hilarious contests as to who could pile up the most verbs at the end of a sentence: “hätten müssen können sollen,” and other such monstrosities worthy of Mark Twain. As I recall, Ted almost always won. At the end of that splendid year in Bielefeld, Ted and I tried to keep countenance, helpless with laughter, as we belted out the German version of ‘Home, Home on the Range’: “Zu Hause, zu Hause auf der Heide/ Wo die Rehe und die Antelopen sich tummeln…”.

Thereafter, Ted and I saw each other at intervals, when we wrote a chapter together on how probability had changed everyday life for the collectively authored book Empire of Chance in Freiburg one summer or at History of Science Society meetings. At the former, Ted and I had to be talked down by our co-authors from various forms of literary folie à deux: only with great reluctance did we agree to strike one of our subheadings about the effects of some quotidien intrusions of statistical thinking: “Insult to Injury.” At the latter, I doubly cursed the program chairs who put Ted and me in competing sessions, often in adjoining rooms: first, because I had to miss Ted’s talk, always an HSS highlight; and second, because I could barely deliver my own, my thin soprano being no match for Ted’s basso profundo reverberating through a thin wall or partition.

I continued to follow Ted’s evolving authorial voice: the brilliant analyses in Trust in Numbers (1995) (my favorite chapter being the one contrasting the haughty noblesse oblige of the French Polytechniciens and the devious cunning of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, driven to cost/benefit analyses by a stingy Congress); the clear-eyed but sympathetic portrait of Karl Pearson (2004). I reread the latter several times, first for the insights into Pearson’s work, then for the insights into the life. The latter were evoked with remarkable sensitivity. Pearson was not an easy man to like during his lifetime and his legacy was in many ways baneful. Yet although Ted’s exquisite sense of irony never failed him as he recounted Pearson’s youthful passions and pretensions and his later feuds and obsessions, Ted wrote with a depth of understanding for human foibles rare in scientific biographies, a genre that tends to polarize into vitae of sinners and saints. To me, this book marked a shift in Ted’s voice, still attuned to ‘nonsense on stilts’ and downright silliness in the historical record, but more reflective, more appreciative of the hardships of being human.

Ted’s deadpan is famous, and he rarely tips his hand in a bald judgment, whether in person or in prose, preferring to let his carefully constructed accounts speak for themselves. Yet the one time I have heard Ted’s voice quiver with something like indignation seems to me to speak volumes about the vision that has informed all his work, from The Rise of Statistical Thinking (1986) to Genetics in the Madhouse (2018). It was at a Wissenschaftskolleg colloquium delivered by a geneticist, who had made grand claims about the future of genetic engineering. In the discussion, Ted pointed out how such scientific swaggering had had a history of causing vast human harm. When the geneticist impatiently waved aside such objections—“We know better now”—Ted retorted, his voice rising uncharacteristically: “Don’t you think some humility is in order?” That intolerance for pretension and arrogance masquerading as knowledge, with what in German is called Besserwisserei, seems to me to inform much of Ted’s extraordinary oeuvre, an earnest current running beneath the ironic surface—the voice of Ted.

Soraya de ChadarevianMORE THAN JUST ABOUT NUMBERS

For as long as I can remember a newspaper clipping was posted on Ted’s office door on the fifth floor in Bunche Hall. Visible to everyone who bothered to stop and look, it read:

“PORTER is more than just about numbers”

What a lucky find! But who, I often wondered, was this other Porter? Perhaps an athlete with impressive stats? The clipping itself did not provide any clue as the source, date or other potentially revealing margins were carefully cut out. Ted himself, when questioned, remained sibyllic about it. A Google search reveals that there was a two-time NCAA collegiate wrestling champion and football player called Dave Porter. Could this be him? Or do these numbers refer to Porter beer? To Porter airport? Or are these the stats of a female body? A Google search for the whole phrase promptly brings up “Porter, Trust in Numbers.” But could it really be that this came from an article about Ted with his last name printed in such bold letters? Perhaps it’s better to ask: what does the newspaper clipping on Ted’s door say about the Porter we know?

Puns amuse Ted. Putting this phrase at the outside of his office door is an invitation to enter with a smile. And where others may try to impress visitors with gold-framed awards and other paraphernalia of personal success, this clipping seemed to want to gently deflect from the numbers and the book that are so often associated with his name. At the same time perhaps, there is a hint that the door (porta in Italian) leads to a place where numbers become reconnected with their historical realities and lose their seeming absolutism, as their rhetoric is carefully analyzed.

Unfortunately, the last time I looked, the clipping had disappeared. When I asked Ted about it, he remembered taking it down but thought it was unlikely that he had thrown it away. I hope he finds it again, not least so I can make sure I remember the phrase correctly. Of course I did not tell Ted why I was so interested in it and I don’t think he suspected anything.

Emmanuel DidierTED’S PERSPECTIVES

One day back in 2017, when Ted came to visit us in Paris, he offered to my wife Aurélie and me a present: a tin can with a label reading ‘Cougar Gold.’

We opened it and, much to our surprise, discovered it was cheese! Cheddar cheese, made at the creamery of Ted’s home state university, WSU. His gift was very considerate and personal but, I have to confess, Aurelie and I were a little worried—how on earth would we be able to thank him after actually eating it!? But then came the real surprise, after we had actually tasted it: the cheese was smooth and creamy and packed with delicious flavor!

This gift, to me, says a lot about Ted. It was thoughtful and funny, the same way Ted is, of course. But it was characteristic of Ted in another way too. It exemplified Ted’s unique way of playing with perspectives. It is the French who are expected to offer cheese to their American friends, not the contrary! But for Ted, the reversal of even the most generally held assumption is always a possibility. So, his present of canned cheese was more than a considerate, funny, and personal gift. It was a demonstration of how things can always be seen from another perspective.

Ted, of course, is an expert at changing around perspectives when it comes to food. He is a refined gourmet and as good a cook as any Frenchman. In Berlin in 2013, when we were both fellows at the Wissenschaftskolleg, Ted and his partner Mary Terrall—a Professor Emeritus of History at UCLA—volunteered to help me make foie gras, with Aurelie overseeing operations. To do this, you need to remove the nerves, a complicated task that involves plunging your hands deep into the fattened goose liver. Some people are grossed out by the process. Not Ted. He found the whole thing highly amusing! The following year, when we relocated to LA, where I was a visiting professor at UCLA for two years, we got to see a lot more of Ted and Mary. One of the first things Ted did to welcome us to California was to invite us for lunch at Mary’s place (we had many delicious meals together, but that day Mary was travelling in Europe). The menu he had prepared included a mixed beetroot carpaccio, scallops with kumquat sauce, and Santa Barbara prawn tempura! His unforgettable cuisine—a word originally borrowed from the French—took our Californian culinary experience to new heights!

But there’s another, more intellectual kind of food I wanted to talk about today, because Ted’s brilliant ability to play with perspectives is also clearly visible in his work. Take his publication Trust in Numbers, especially chapter seven, which I assign my students every year. The chapter shows how the US Army corps of engineers went from having little sway over political decision-makers—especially compared to the French engineer corps, the Ponts et chaussées—to becoming a powerful political voice via quantification-based cost/benefit analysis. In other words, the Army engineers’ ability to make ‘objective’ decisions gave them power in the political arena. Contrary to the belief whereby quantification is a ‘tool of power’ to be wielded by the government, the chapter concludes that statistics are also and at the same time a ‘tool of weakness’ to be wielded by less powerful hands—in this case that of the engineers. These ‘weaker’ parties are able thus to resist and even, at times, to gain the upper hand. Ted’s line of reasoning turns Foucault upside down. It is not a criticism of statistics but rather a perspective placing the focus on the liberating properties of statistics. This postulate is at the heart of the concept of ‘statactivists,’ a term we coined with Isabelle Bruno, an associate professor in political science at the University of Lille, and the artist Julien Prévieux. Statactivists are activists who use quantification tools to defend their cause, and who frequently have to invent parts of their statistical methods. Most often, they are neither specialists nor bureaucrats, like the staff of the Army Corps of Engineers. However, like these latter, they find themselves in a weaker position and make use of quantitative tools to try to gain greater power and freedom.

Here is another example of Ted’s ability to flip perspectives. In the late 1990s, while I was at the Ecole des Mines with Bruno Latour, we invited Ted to the CSI in Paris to give a talk. After the seminar, while we were out for drinks with Ted, Fabian Muniesa, and a number of other participants, Ted all at once turned to Fabian and asked without warning or a lead-in, “So tell me, Fabian, what exactly do you mean when you say that the economy or statistics ‘performs’ the world?” What a question! There was a consensus at that time in Paris regarding the concept, with which we were all supposedly familiar and in agreement. But again, Ted, who is clearly convinced of the social impact of quantification, was suggesting another more realist perspective of how numbers behave. Observing Ted’s falsely naïve question regarding this commonly accepted notion, one that he himself never used, inspired me to play with it as well.

Lastly, to speak about Ted inevitably brings me to his relationship with language. In all of his written work, his mastery of language is clearly visible. I am constantly amazed by his skillful use of narration, story arcs, and eloquent examples, by his attention to detail and precise use of vocabulary. I always tell my students in France: “Pay attention when you read Ted Porter. He writes in English not in basic Globish.” I particularly admire the way Ted seamlessly knits various perspectives into a subject matter. His texts appear to be produced from a single cloth but, in reality, are comprised of multiple stitched-together viewpoints. These perspectives are so skillfully articulated that the reader isn’t immediately aware he has switched from one perspective to another.

His masterful use of English goes hand in hand with his taste for foreign languages. In Berlin, where we were immersed in French, German and English, Ted and I often had amusing conversations about various linguistic ‘fun facts.’ We’d play with English language homographs—desert vs. desert, close vs. close, and content vs. content—or laugh about our different pronunciations of the German genau, pronounced ‘Ge-now’ in Ted’s mouth and ‘Genaho’ in my more Gallic attempt. In LA, Ted coined the portmanteau term ‘Didina’ in reference to our respective last names, ‘Didier’ and ‘Slonina.’ Our very spacious home was therefore dubbed ‘Chateau Didina’ by Ted. But even more impressive to me is the fact that his mastery and love of words and linguistic cultures can be seen in his unique ability to analyze and unpack the very specific jargon of mathematics and statistics!

To me, Ted’s love of different languages and his taste for switching up perspectives are two sides of the same coin. Because languages—including the languages of quantification—are tantamount to opening perspectives on the world, and Ted, as a true cosmopolite, has a genuine love of embracing all of them, one after the other.

Wendy EspelandFACTS

Ted is generous. Ted is loyal. Ted is meticulous. Ted is honest. Ted wears a lot of khaki pants. Ted is an amazing friend. If you need a last-minute speaker, Ted has his bag packed. It could be Jersey. It could be Rome. He’ll be there. And now…. A Few Fun Facts About Ted.

-

I can make 64 words from Theodore M. Porter. The most notable include: Meteor Poem Method Mother Terror Order

-

Ted played the tuba in the marching band.

-

Ted does an amazing impression of a turkey.

-

Ted puts the buff in opera.

-

There is a Ted Porter elementary school in Fontana California.

Haiku for Ted

to our most unflappable friend.

We all trust in Ted.

ODE TO TED

HIS IMPENDING

RETIREMENT

SEPTEMBER 16, 2022

In Ted we Trust

to teach us Objectivity

Mechanical, yes, but also

Historicity.

His Motto is: Be Fair

to bolster our Receptivity

in Ted we Trust,

to teach us Scholarly Humility.

In Ted we Trust

to help us grow Community

for Freaks like us, to foster Nerdy Unity.

Cost-benefits. Annuities. Eugenics and

Insanity. Ted Finds a way to celebrate

Humanity.

In Ted we Trust.

Love from,

Friends, Scholars, and assorted Personalities

Gerd GigerenzerALL IN THE NUMBERS

Back in 1982 Ted and I met for the first time at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Bielefeld for a year-long workshop on the Probabilistic Revolution.1 We were among the youngsters in a group of eminent scholars, and ended up as co-authors of the volume The Empire of Chance.2 The Empire’s currency is statistics, backed by objectivity, prestige, and trust. While in Bielefeld, Ted worked on his first book, The Rise of Statistical Thinking 1820-1900, in which he analyzed how the language of probability transformed the thinking of social scientists, biologists, and physicists. For me, the year at the Center was life-changing, expanding the small world of a psychologist to the large world of the history of science.

What can I contribute to this celebration of Ted and his achievements? My first impulse was to write about his brilliant gift of parodying the German language by amassing scores of verbs at the end of sentences, or about his unique technique at the ping-pong table. But instead I will provide a few examples that show why his topic, the rise of statistical thinking, remains so timely in the twenty-first century. By now, numbers have become the language in which many politicians, journalists, and the general public talk. But understanding these numbers is another thing.

“We send the EU £350 million a week. Vote Leave.” That shocking figure, displayed on the Leave Campaign’s iconic red bus during the 2016 Brexit referendum, may have tipped the narrow balance in its favor, resulting in 52% votes for (versus 48% against) leaving the EU. However, the figure was unrealistically high and ignored what the UK then recouped from the EU. Had it been expressed as 75p per day and per person, as British statistician David Spiegelhalter once proposed, it would have startled few voters. Since time immemorial politicians have been accused of deliberately twisting the facts. But the question is, do they actually understand statistical numbers?

Four years before the Brexit referendum, the Royal Statistical Society (RSS) investigated this question with the voluntary help of 97 MPs. By no means did the MPs form a representative sample, and most of them felt confident dealing with numbers. The first question posed to them was:

If you toss a fair coin twice, what is the probability of getting two heads?

If you are not sure, you are not alone. Barely 40 percent of the MPs correctly figured out that the answer is 1 in 4, or .25. Almost half of the MPs (45 of 97) believed the probability to be .50. Conservatives fared better than Labour MPs. When this degree of innumeracy became known, 220 candidates seeking to enter the House of Commons signed up for a workshop on how to interpret statistics in public life.

Ten years later, in 2022, the RSS repeated the test with 101 MPs. Statistical thinking had improved: This time, 50 percent of Conservatives and 53 percent of Labour MPs got the answer right, although newly elected MPs performed worst.3 Once again, the 2022 group was self-selected; in a representative sample of the UK adult population, only 25 percent found the correct answer.

What about Covid-19 statistics? After all, the numbers were what fueled our hopes and fears during the pandemic. In their 2022 test of MPs, the RSS also posed this question:

Suppose there was a diagnostic test for a virus. The false-positive rate (the proportion of people without the virus who get a positive result) is one in 1,000. You have taken the test and tested positive. What is the probability that you have the virus?

The answer is that no correct answer is possible on the basis of that information alone. One would also need to know the hit rate of the test, and the base rate of infected people. Only 16 percent of MPs realized that; the others came up with a probability such as 999 in 1,000. This error is known as the prosecutor’s fallacy, that is, confusing the probability of a positive test given no infection (or a DNA match given no guilt) with the probability of no infection given a positive test (or no guilt given a DNA match). On this particular question, the MPs were hardly better than the general UK public, 15 percent of whom responded accurately. My point is not simply lack of statistical literacy, but that most do not suspect they suffer from it. For instance, former prime ministers Tony Blair and Theresa May publicly presented health statistics that they systematically misunderstood. 4 The extent of statistical illiteracy resembles a raging pandemic that has gone unnoticed.